Fertility by Design?

Technology matters, but won't save us: an extensive response to Ruxandra Teslo's "Fertility on Demand"

You should read Ruxandra Teslo ‘s recent piece for Works in Progress on fertility. It is one of the more complete, more careful, and more interesting expositions of the techno-optimist approach to fertility. Ruxandra is a good writer and clear thinker which is to her credit, and it also means her article is well worth criticizing, because it’s very clear in its claims, which I believe are incorrect in many places. In this article I will argue for why techno-optimism about fertility is a mistake. My argument will proceed in three parts:

Part 1: Motherhood Penalties

1.1 Ruxandra misunderstands the estimand for the study she relies on for age-varying motherhood penalties

1.2 Motherhood penalties are totally insensitive to policy and in fact overwhelmingly linked to leisure consumption

1.3 Motherhood penalties are often lowest for the youngest women

1.4 Motherhood penalties arise entirely from women’s own beliefs and preferences about care of children and duties at home

1.5 Motherhood penalties cross-sectionally predict low fertility, but maybe not for the reasons we might think

1.6 Longitudinally, smaller motherhood penalties predict LOWER fertility (because motherhood penalties are actually just a proxy for care attitudes which are also fertility-correlated)

Part 2: Reproductive Technology

2.1 Expanded access to reproductive technology has a precisely-estimated null effect on fertility.

2.2 Even with modern reproductive technology, ASFRs for older women are below historic levels.

2.3 Widespread egg freezing is actually more socially costly than doing IVF later on, because most women who freeze their eggs will never use them: it is highly inefficient insurance.

(paywall is here)

2.4 Males also have a fertility timeline, so in theory you’d really need frozen eggs and frozen sperm.

2.5 The most binding fertility timelines are not about biological capacity, but rather about the social life cycle of marriage, work, and retirement; or about the healthspan, which is not rising much anymore.

2.6 The highest-yielding potential reproductive technologies are actually better identification and treatments for early-in-life reproductive issues: PCOS, endometriosis, recurrent miscarriage, thrombophilias, antiphospholipid syndromes, etc.

Part 3: Fertility Writ Large

3.1 Ruxandra erroneously suggests that fertility decline can be addressed by helping highly educated women have more children.

3.2 In fact, the vast majority of fertility decline in the last 20 years is among less-educated women who still have kids rather young: biological infecundity isn’t the issue here.

3.3 A key reason people delay fertility is because of ignorance, not that they actually weighed career options.

3.4 We can fix ignorance.

Part 1: Motherhood Penalties

1.1 Ruxandra misunderstands the estimand for the study she relies on for age-varying motherhood penalties

The paper Ruxandra Teslo cites is this one. It’s nice but misleading. See, it uses an event-study framework popularized by Henrik Kleven which works like this: we compare women at a given age who had a baby to ~someone else and see how their trajectories change. In Kleven’s famous framework, we are comparing women who had a baby to their husband's’ income trajectores, and/or similar-aged women who didn’t have a baby at that time. This paper rather compares women who had a baby earlier in life vs. later in life.

Kleven’s approach is tenuously, provisionally, kinda-sorta accepted in the literature as quasi-causal. Yes, women’s pre-birth income may be endogenous to expected future fertility decisions, but exact timing of birth should be semi-endogenous to this kind of thing, right? I can tell you, I have a paper in review right now using the Kleven event-study framework and the reviewers have actually demanded we not treat it as causal, even though my sense is much of the economics literature believes it is.

But the paper Ruxandra Teslo cites isn’t even that! It’s comparing younger to older moms, who are obviously not the same.

A woman who has a first baby at 22 is extremely different from one who has a baby at 32. The paper tells us nothing about what that 22-year-old-mom’s motherhood penalty would have been if she had waited a few years later. All it tells us is that women who have babies later stay in work more. Is that causal? Well it depends on what the motherhood penalty is. And that brings us to….

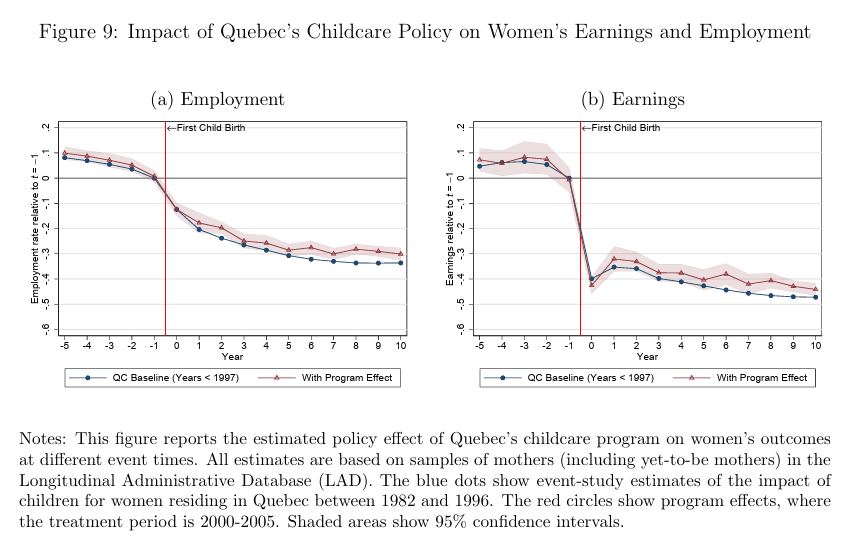

1.2 Motherhood penalties are totally insensitive to policy and in fact overwhelmingly linked to leisure consumption

If motherhood penalties are caused by greedy jobs with high time demands, then providing women tools to manage time demands (mat leave, childcare, etc) should reduce motherhood penalties.

The reality? Massive childcare expansions have basically zero effect on motherhood penalties.

And this is general: decades of work-life balance reforms in Austria had zero effect.

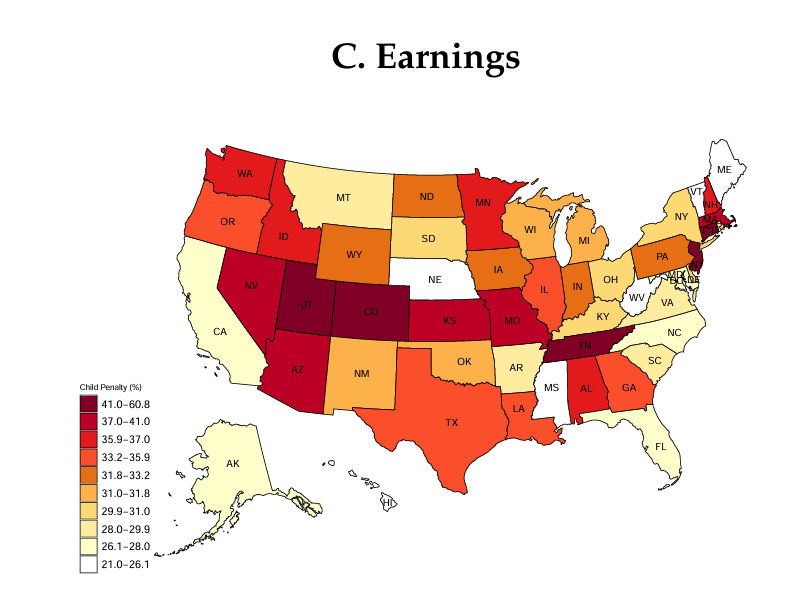

Why is this? We’ll come to that, but first let’s understand who has motherhood penalties. The best paper for this is Kleven’s study of the U.S. Here’s motherhood penalties by state:

Kinda sorta looks like more conservative places have a bit bigger penalties, but it’s not extremely clear? Now let’s look by groups.

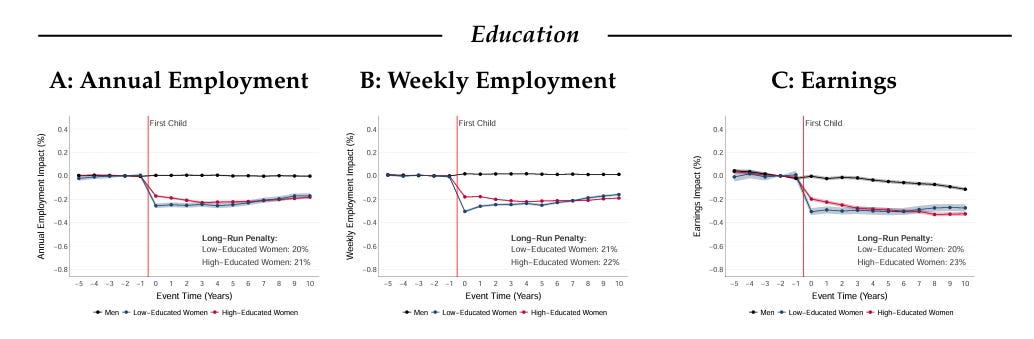

Education:

Higher-educated women have smaller short-run marriage penalties but larger long-run ones. That’s consistent with Ruxandra Teslo ‘s “greedy jobs” thesis. But…

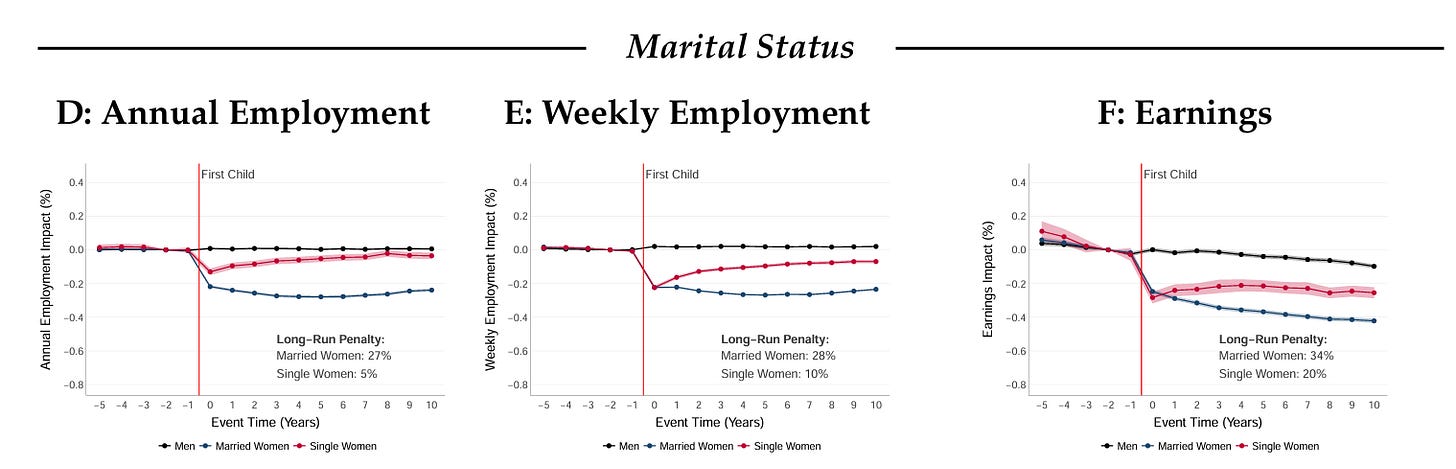

Marriage:

Motherhood penalties are overwhelmingly driven by married women. They are twice as large for married women as for single women. That’s fascinating! We wouldn’t expect a “greedy jobs” hypothesis to have a waaaaaaay stronger heterogeneity by marriage than by education. If it’s “greedy jobs” there should be huge educational differentials, but in fact those differentials are modest. Instead there are huge marriage differentials. What gives?

Race:

It’s mostly white women having motherhood penalties. White women’s penalties are almost three times as large as black women’s!

Here’s what’s going on: unmarried parenthood is more common for black moms, and even married black moms have lower-earning husbands. In other words, motherhood penalties mostly exist for women who have rich enough husbands to choose to exit the labor force to spend time with their kids.

When we observe this kind of elasticity pattern where rich-people-do-it-more, we call it a luxury good or a superior good. In industrialized countries, there is good reason to believe motherhood penalties are a luxury good.

DUH!!!! Ballerina Farms lady is consuming luxury! She exited a career with earnings to be with her kids because her husband is super rich! This is all the Instagram momfluencers! They have wealthy husbands, so they exit work, and have a “motherhood penalty.”

1.3 Motherhood penalties are sometimes lowest for the youngest women

Ruxandra Teslo says motherhood penalties are highest for the oldest moms. And I will say this is mostly true. But… a recent paper throws it into doubt, or at least complicates it. Early fertility only penalizes wages for women who go on to get educated. But a recent study suggests that for less-educated women, there’s no wage benefit to delay.

It’s hard to know what to make of this: the paper Ruxandra Teslo cites uses Danish data; the paper I cite is U.S. data. But the Danish case chains everything to age 25 and aggregates all pre-age-25 births, so it’s a bit tricky to know what it would show for actually young births (sorry kids, 25 isn’t young). Regardless, the point is that it just is not intrinsically true that delayed fertility is always the path to maximizing lifetime earnings trajectories: for less educated women, early fertility can be a no-worse-than-alternatives plan! (this is mostly because they have low incomes no matter what and can’t afford to exit work at any stage, because, as we established, motherhood penalties are a luxury good)

1.4 Motherhood penalties arise entirely from women’s own beliefs and preferences about care of children and duties at home

Now, if the studies above actually don’t tell us that motherhood penalties are all about career timing, and if motherhood penalties actually are associated with women who have the most support for their childrearing… what should we make of child penalties?

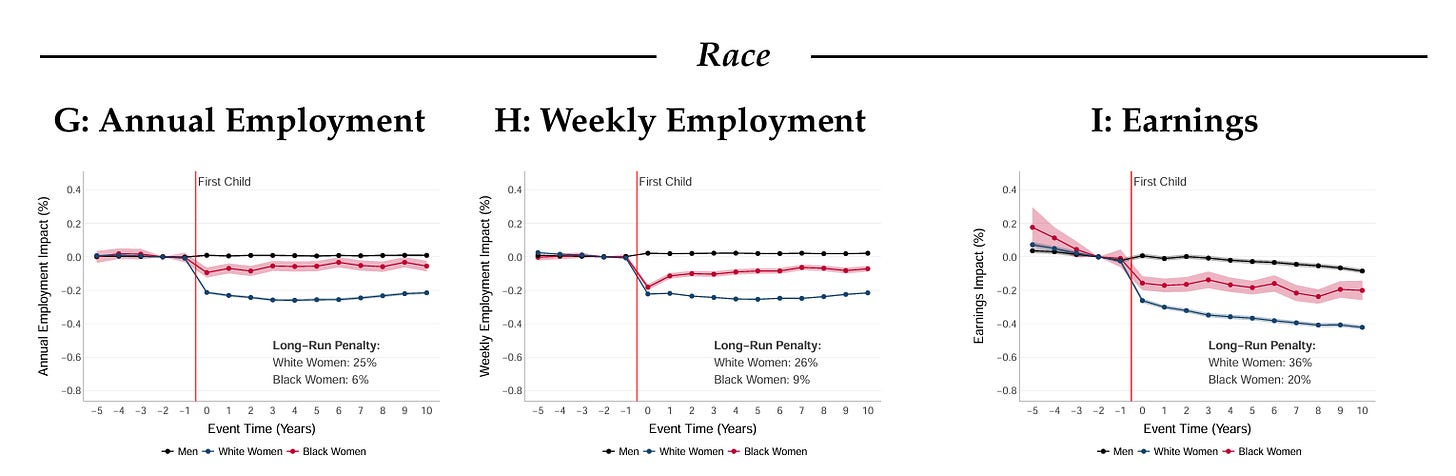

Well, the leading motherhood penalty-researcher, Henrik Kleven, is abundantly clear about what he thinks is going on. He says motherhood penalties are 100% about women’s own preferences around childrearing and gendered labor. First, he notes, as I did above, that major policy interventions appear to have little or no effect on motherhood penalties. Second, some specific variables turn out to be very correlated with motherhood penalties!

For example:

U.S. states with more gender-progressive social attitudes among women have smaller penalties: waaaaay smaller. The most progressive states have penalties just 1/3 the size of the most gender-traditional states (though this is partly due to underlying demographic differences).

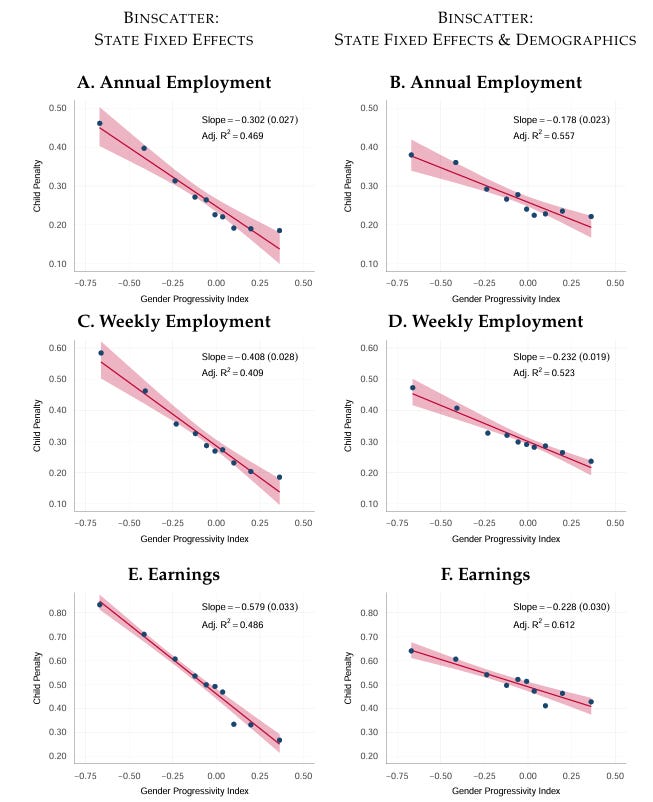

Does this mean state-level gender norms force women to stay home? Actually, no. Because we can look at women who move away from home vs. stay at home. Here’s what that shows:

As you can see, there’s an extremely strong correlation between child penalties among women who remain in their state of birth vs. women born in that state who move away. Women carry propensities to larger penalties with them when they move. So what are motherhood penalties? They seem to be individual-specific, portable traits. Perhaps… beliefs.

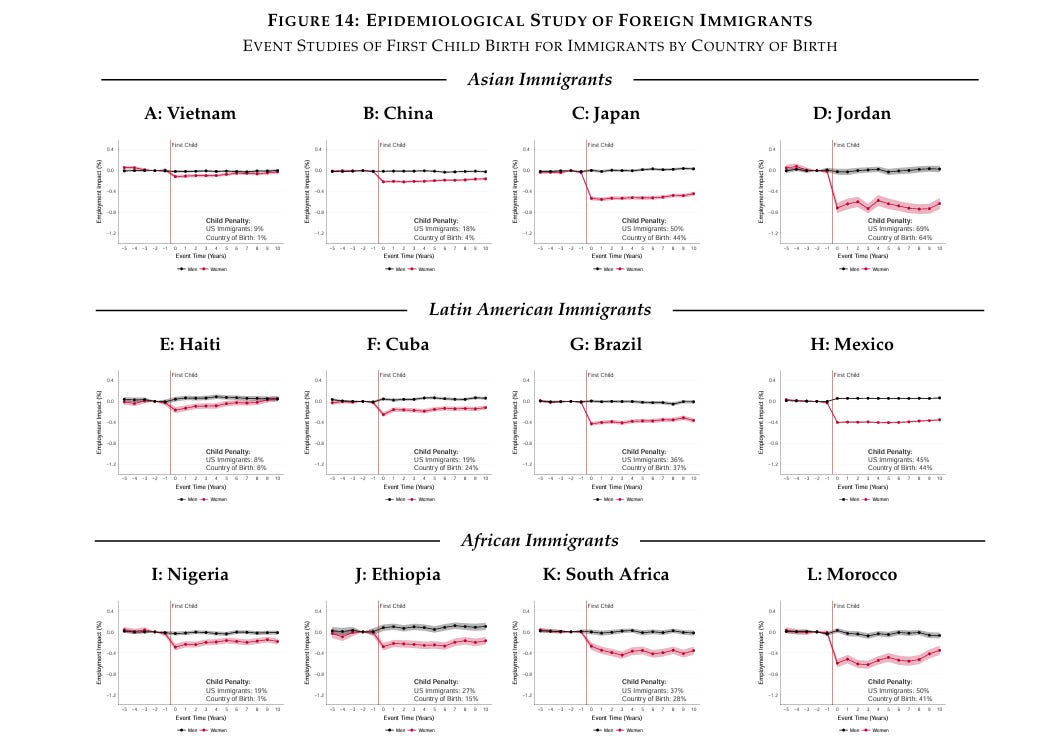

In the same sample, here’s child penalties by immigrant country of origin. See what’s going on? Massive differences! That’s because these women have different beliefs about motherhood and work.

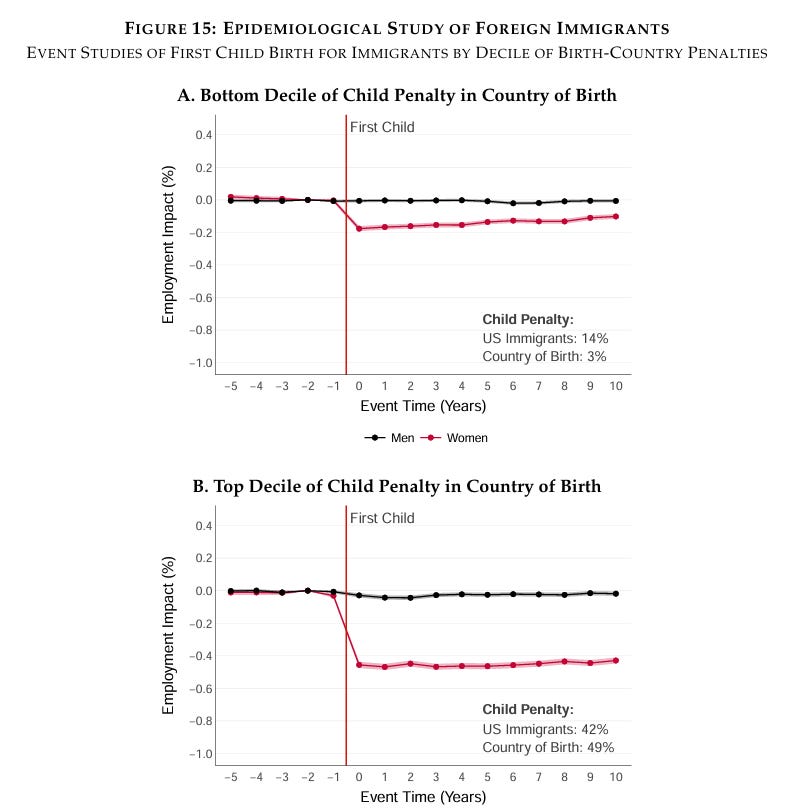

Here it is for top/bottom decile motherhood penalty countries:

Women born in countries with big motherhood penalties themselves have big motherhood penalties when they move to America, and vice versa. Motherhood penalties follow you across international borders!

Because they are inside you! Within the U.S., one state has way bigger motherhood penalties than others: Utah. It’s not at all mysterious why this is: it’s LDS family norms for LDS people. And while those norms could be seen as good or bad, the point is it’s not that Utah has greedier jobs than other places.

1.5 Motherhood penalties cross-sectionally predict low fertility, but maybe not for the reasons we might think

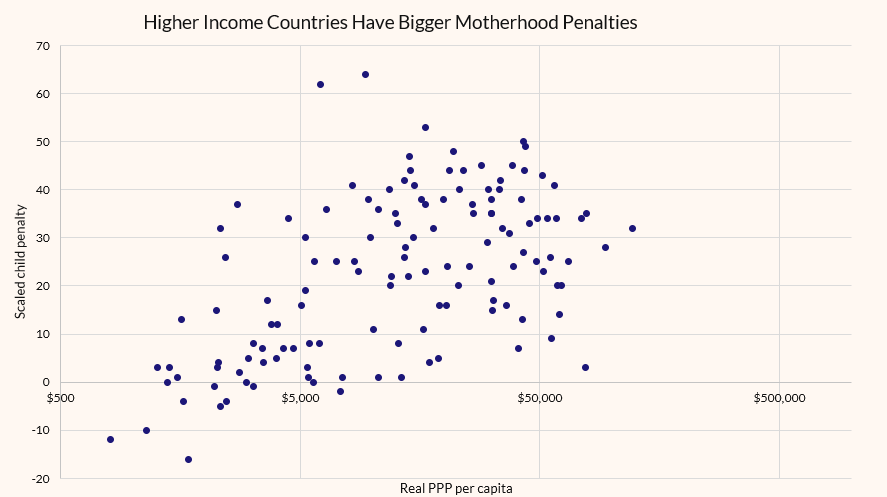

Ruxandra Teslo cites this piece from Boom which suggests bigger motherhood penalties mean lower fertility. But Phoebe Arslanagić-Little , the author of that piece, correctly caveated “Correlational data of this kind should not be used to draw definitive conclusions (the correlation is only -0.43 and the R2 is 0.1905).” And the figure she shows is just high income countries. So let’s ask: what’s the child penalty:income correlation at various income levels?

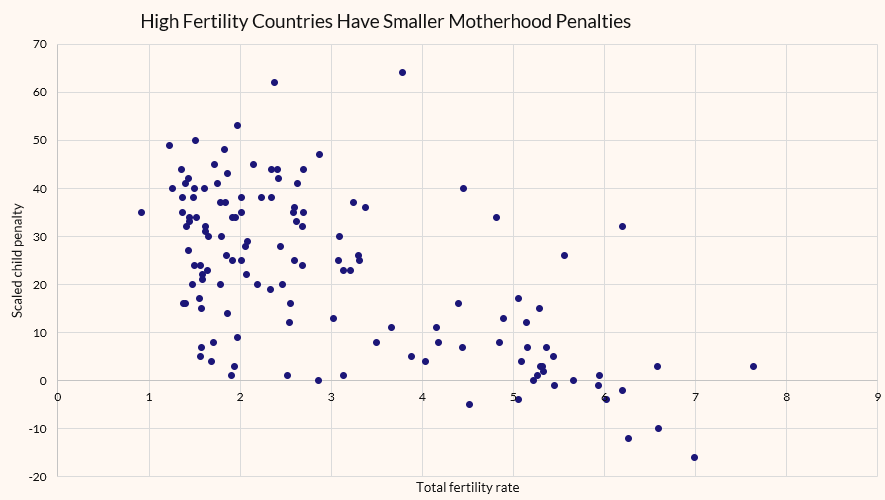

We can see that higher income countries have bigger child penalties. So on some level, any penalty:fertility relationship risks confounding by other factors. Regardless, how does the penalty:fertility relationship look?

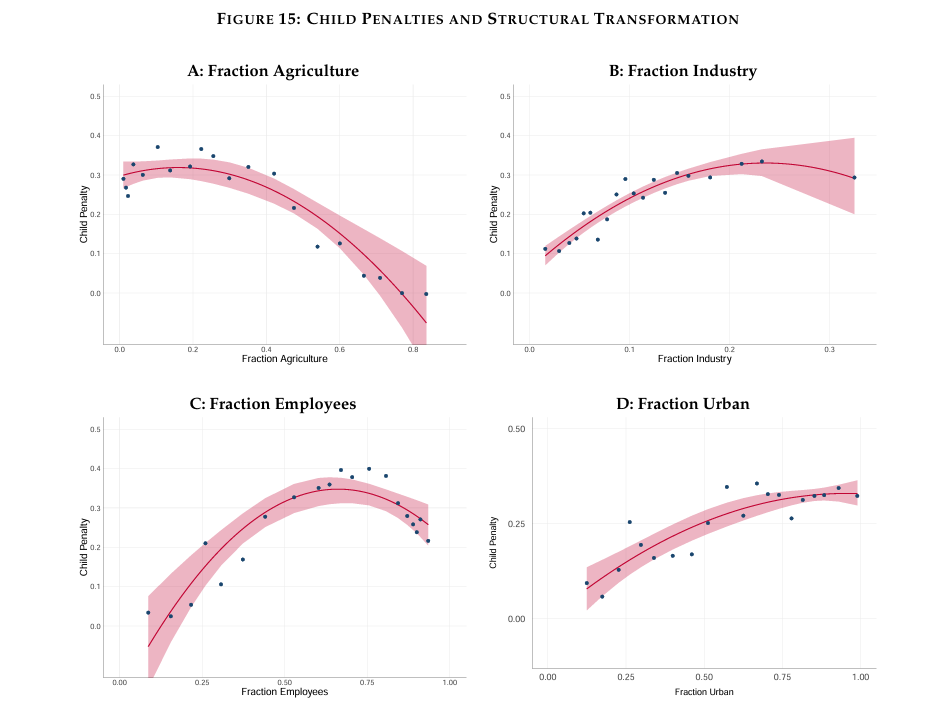

Well, higher-fertility countries DO have smaller motherhood penalties! Is this because of “greedy jobs”? Well, here’s motherhood penalties across bins of countries of various traits:

The clearest evidence here is about the shift away from agriculture. In countries with lots of agriculture, motherhood penalties are small, largely because agriculture is basically “family work” to begin with. I have a forthcoming study where we show evidence that the line between women’s domestic work and women’s agricultural labor supply is often extremely fuzzy, and so “small motherhood penalties” are just an optical illusion: in agricultural, low-income societies, non-agricultural formally-employed women have penalties on the same scale as westerners.

But these effects mostly occur with the shift from 90% agticulture to 20%, or from 0% urban to 70%, or 0% employees to 60%. These changes are not associated with the “extreme end” where we would expect greedy jobs to proliferate.

If I use a multivariate model, I’ll tell you including PPP eliminates almost 30% of the effect of the child penalty (though the child penalty also eliminates a large part of the effect of PPP).

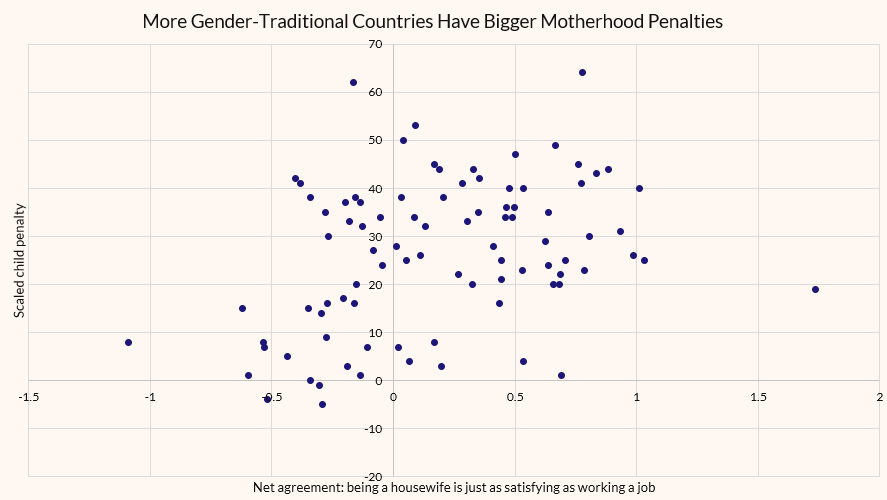

In other words, we saw that within countries penalties were basically a proxy for beliefs. Cross-nationally they are basically a proxy for agriculture. But what about values? Well, using the WVS/EVS dataset, we can see how penalties relate to some gender-work attitudes. For example:

Motherhood penalties are bigger when more women believe being a housewife is satisfying. This is super important since it kinda calls into question what we mean by a “penalty.” It’s only a penalty if women dislike it! But if the reason some countries have bigger motherhood penalties is some kind of vector of agriculturalism + women’s own preferences for being at home, is it right to call it a motherhood penalty? Note that, above, I’m using only WVS/EVS responses since 2000 by women ages 18-44.

Just for reference, in a multivariate regression where PPP and gender-traditionalism are used to predict the penalty size, the effect of 1 standard deviation change in gender-traditionalism is twice as large as one standard deviation change in PPP. Motherhood penalties emerge primarily from families, including women themselves, choosing to stay home and raise their children even though other women in their societies with other attitudes choose not to do so. This is important: we aren’t talking mostly about a situation where women are being forced to stay home. We’re mostly talking about women’s own preferences for themselves here. Perhaps those questions arise from some underlying inequity, that’s possible, but on some level I think we have to grant peoples’ actual-existing preferences meaningful epistemic and moral priority.

1.6 Longitudinally, smaller motherhood penalties predict LOWER fertility (because motherhood penalties are actually just a proxy for care attitudes which are also fertility-correlated)

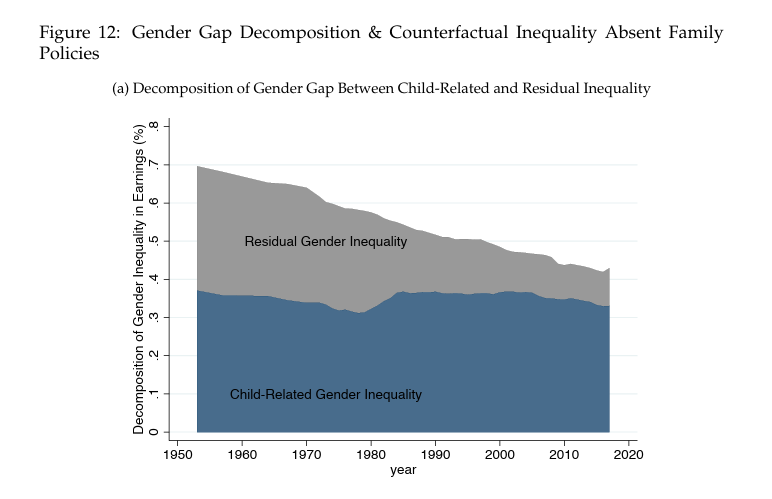

We don’t have change-over-time in motherhood penalties for lots of places, but we do have it in a few places. In Austria, the motherhood penalty has been stable or shrunk slightly over time:

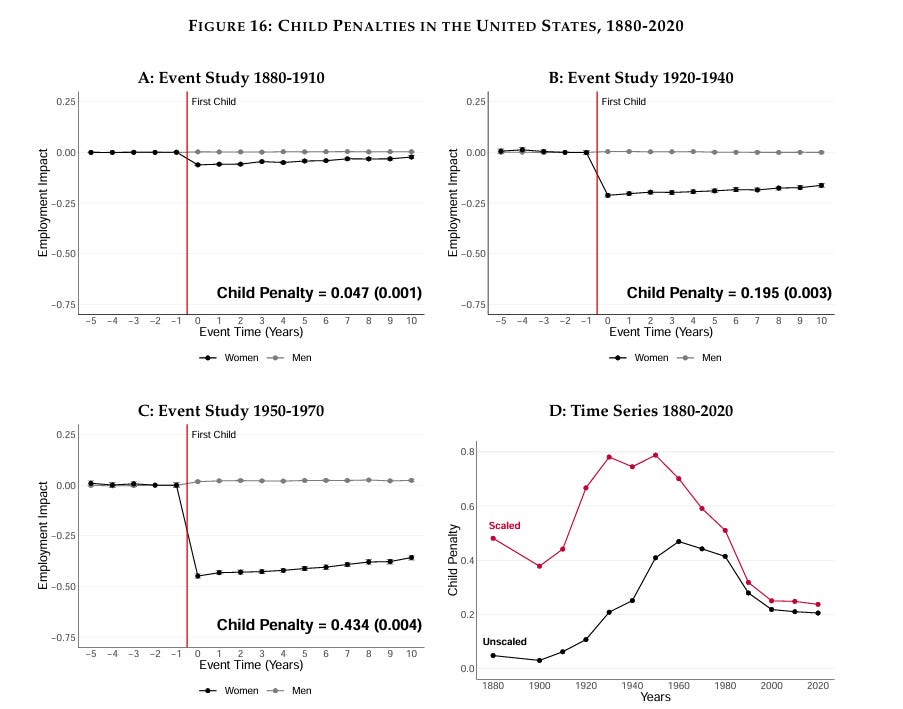

In the U.S., depending on if you prefer unscaled or scaled estimates, there could be some debate. Personally I prefer the scaled estimate as it represents something closer to a behavioral parameter: the odds an employed woman loses her job after a baby.

You can see that the scaled motherhood penalty rose between 1910 and 1930, and remained high through 1950, i.e. the “baby boom” occurred alongside high motherhood penalties. Then the motherhood penalty plummeted and got way smaller between 1950 and 2020. The motherhood penalty in the 2020s is at the lowest level it has ever been at it. So is fertility.

So color me quite skeptical that major changes in the motherhood penalty are actually in the driver’s seat on fertility.

TL;DR- Motherhood penalties are mostly measures of women’s attitudes about gender, work, and childcare; may not even always be properly described as “penalties”; and are rather weakly related to fertility.

Part 2: Reproductive Technology

2.1 Expanded access to reproductive technology has a precisely-estimated null effect on fertility.

The next big theme in Ruxandra Teslo’s piece is reproductive technology. She’s an optimist about it. But she really shouldn’t be! Making current technology virtually free of charge has a known near-zero effect on birth rates! From multiple different cases of policy changes in this area, we actually have a pretty good grasp of what would happen if, for example, insurance companies start covering egg freezing. What happens is young women freeze more eggs, they feel less urgency about reproductive timelines, first birth rates at young ages drop even more, and while first birth rates at older ages rise slightly more to compensate, higher-parity birth rates fall at older ages as the incoming parity-ratios of new cohorts are more inflated at the zero parity to begin with, and even with IVF timelines are not infinite. The upshot is expanded IVF access doesn’t reduce fertility, but it doesn’t increase it either.

Moreover, Ruxandra Teslo has a footnote where she notes a recent study which shows that childbirth has no motherhood penalty at all when comparing successful to failed IVF. She’s correct that we shouldn’t totally generalize from this case to motherhood penalties all across society: but this does wreck her argument about using IVF to compensate for greedy jobs. Women in the current IVF client base don’t have any motherhood penalties anyways! Why? Because “older women ethically comfortable with IVF and with the money to pay for it” are a group that already scores super low on the values we know are predictive of motherhood penalties, such as believing that moms ought to stay home. Most of these parents will make heavy use of childcare centers, for example, rather than being stay-at-home parents.

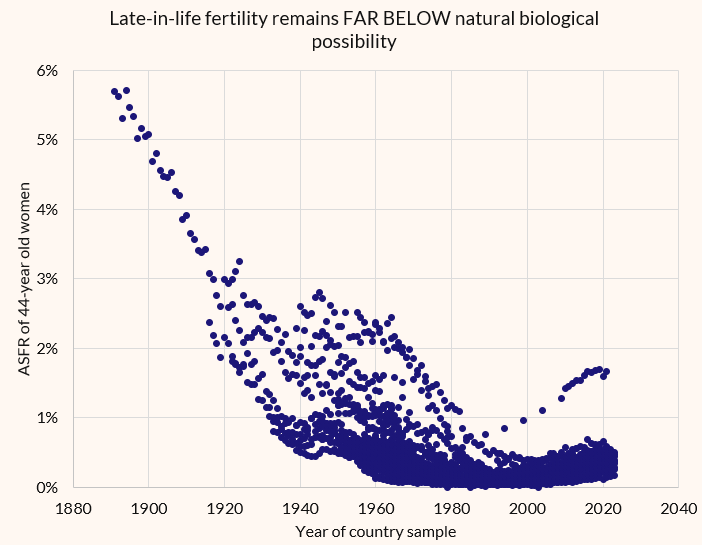

2.2 Even with modern reproductive technology, ASFRs for older women are below historic levels.

From all the talk about IVF, you might assume that current birth rates for older women are somewhere close to their biological limit, like the only thing holding 44-year old women back is that they just can’t have kids anymore.

But… this is nonsense. Using all data in the Human Fertility Database, here’s the % of 44-year old women who had a baby in the next year across all countries HFD has data on, over time:

Today, 44-year old women in the mostly-Western-world sample here from HFD average about 0.4 babies per year per 100 44-year-old women. In 1960, before IVF was invented, they averaged 0.7. In 1940, 1.1. In 1900, somewhere between 3 and 5. Despite modern medicine, older women today have about 90% lower birth rates than older women had a century ago.

Now, that one outlier you see? That’s Israel. Israel has tons of IVF. You may be tempted to say, “See Lyman! IVF! It’s amazing!” We’ll come back to that.

The general decline in late-in-life fertility isn’t because of a change in biochemistry. It is because desired family size has shrunk, because peoples’ ideas of their lives have changed, and because even if you can have a baby at age 48, would you really? Maybe in 1885 you do, because you still have religious norms about fertility, and even if you die before you kid reaches maturity, you trust you’ll be together in heaven. But today? Not so much. The constraint on late-in-life fertility rates today is not IVF, but willingness to try at all. The share of women in their 40s who even want to have additional children has declined over time!

2.3 Widespread egg freezing is actually more socially costly than doing IVF later on, because most women who freeze their eggs will never use them: it is highly inefficient insurance.

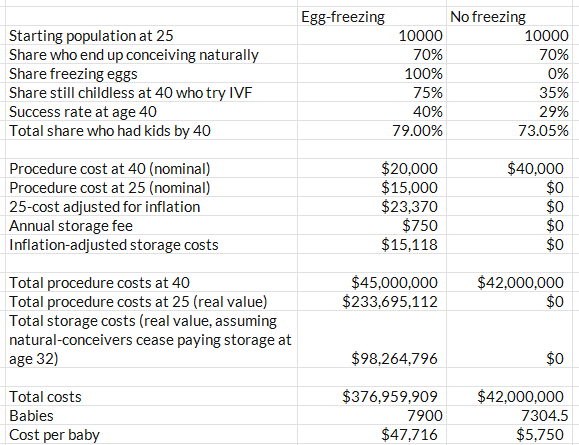

Ruxandra Teslo has done great work on the success rates of IVF and egg freezing. But she doesn’t seem to realize how awful the math is on it. So let’s do the math.

Suppose we have two options: freeze eggs at 25 to use in IVF at age 40 unless a woman conceived naturally, i.e. as insurance; or, no freezing eggs, and if woman doesn’t conceive naturally, she does fresh IVF at age 40.

What are her success odds and her costs? For statistical simplicity, we will care 10,000 women in each of these scenarios. Here’s the full math:

My major assumptions are: 1) 70% of childless 25-year olds will conceive naturally by age 40, 2) 70% of women who freeze eggs and have not yet had children will try IVF using their frozen eggs, 3) just 35% of childless women at age 40 who have not frozen eggs will try IVF, 4) success rate for frozen eggs is 40%, for non-frozen is 29%, 5) the nominal cost of initial freezing and future usage is LOWER than the nominal cost of doing it all at once, 6) storage fees are in the industry-typical range.

The result is that the egg-freezing crowd pays a real inflation-adjusted cost of $377 million vs. $42 million for the non-freezers. The egg-freezing crowd does have more first births: 7900 vs. 7300, a nontrivial difference! But at literally 10x the price!

I show “cost per baby” distributed across all babies there. But we can also ask “cost per IVF baby.” The cost is $418,000 per IVF baby in the egg-freezing case, and $138,000 per baby in the other case. And remember, this is not accounting for any effect of subsidized-IVF leading women to delay fertility more and thus lose out on higher-parity births! Once we account for that, it turns out that reproductive technology has, as would be expected from the precise null finding on overall fertility, worse cost effectiveness than conventional pronatal policy.

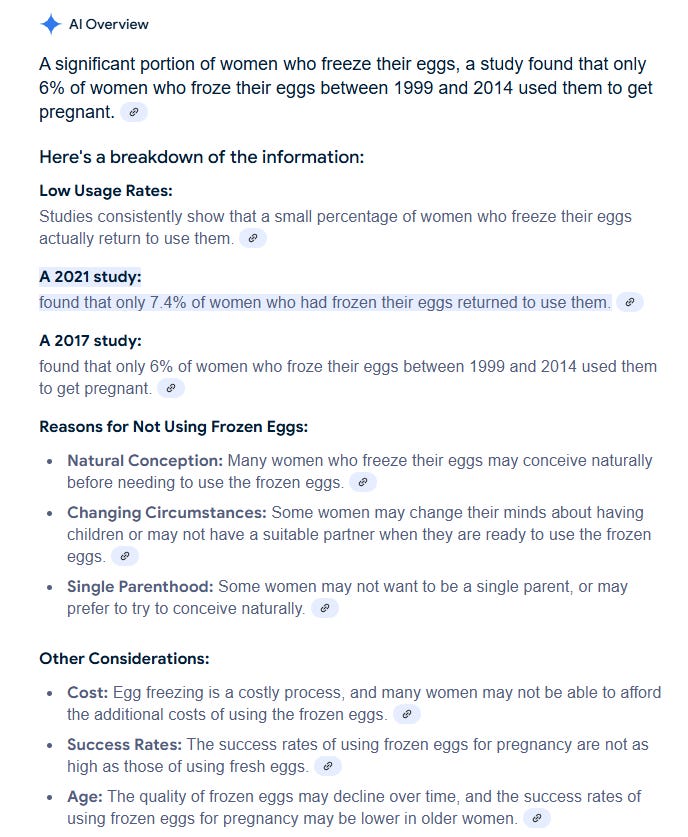

Why is egg freezing so inefficient? Simple: most women who freeze their eggs never use them. Egg-freezing is kind of like insurance for fertility, most people never use their term life insurance, and most people never use their frozen eggs. This is empirically true:

The simple fact of the matter is that a regime of widespread egg-freezing pours a crapton of money into IVF clinics for not that many babies.

Now that’s maybe blackpill enough on IVF, but it actually gets worse! Remember how I mentioned studies show IVF doesn’t boost fertility? Well, those studies cover the period 1980-2015 or so. But egg freezing has only recently started to explode in popularity. In other words, we know that IVF without egg freezing which makes delay and insurance dynamics even easier and cheaper had no benefit to births. Now imagine a situation where huge shares of women are dropping a massive share of their 25-year-old-net-worth on eggs they never use. It’s IVF, but with a huge negative asset shock right at the years when asset accumulation should be taking off exponentially. It’s a horrible trade! We don’t want to put more liquidity constraints on young people! That slows life timelines even more!

Egg freezing simply is not a reasonable path forward at the societal scale, and is probably only a rational bet for women absolutely certain they want kids and extremely pessimistic about their odds of marrying before their early 30s.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Lyman Stone to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.