How Western Dreams Became Demographic Nightmares

Saying the name of the actual idea at the root of falling fertility: developmental idealism

Fertility is falling all around the world and people want to know why. It’s common for people to say things like “We don’t know why” or “It’s a mystery why.” The people saying these things are usually not demographers and often have not read many demographers. I’m here to tell you that we in fact mostly know why fertility is falling, and that a fairly small number of variables can account for quite a lot of the change. It’s not rocket science.

I want to keep this post almost-semi-kinda-reasonably-lengthed so I’m not going to deal with every single random explanation out there. Instead, I’m going to lay out five basic arguments.

But first! This is my first Substack post. I imported over a large Medium archive. I have set up paid subscriptions. I’m going to make one thing clear from the start: I anticipate doing one maybe two posts a month here. They will mostly be deep dives into eccentric fertility- or survey-related topics I care about, or case studies of countries that interest me. If you subscribe and pay me money, I make absolutely zero promises to produce a large volume of content. Furthermore, I like making stuff free. I am never going to paywall more than 50% of any article. And if you have a Substack, I’m more than happy to swap gift subscriptions with you. I have other jobs that pay my bills, I’m Substacking for an outlet for a particular range of my demography interests, with fairly limited financial needs.

Five Basic Arguments for Understanding Fertility:

Data has to be read “vertically” (longitudinally), not “sideways” (cross-sectionally)

No variable comes anywhere close to “survey-reported fertility preferences” in terms of ability to explain national fertility trends in the long run

People develop preferences through fairly well-understood processes related to expected life outcomes and social comparison

The name for the theory which best stands to explain why preferences have fallen is “developmental idealism.”

and after the paywall break

Countries with fertility falling considerably below desires are doing so primarily due to delayed marriage and coupling

TANGENTIALLY RELATED BONUS: Education reduces fertility largely by serving as a vector for developmental idealism in various forms, not least by changing parenting culture.

1. Never Read History Sideways

Suppose you are a country with low fertility, say, Italy.

Suppose you want to do something about that problem.

How would you know what you should do?

The obvious intuition many people jump to is to look at some kind of comparison of high and low fertility countries. Here’s one such comparison, comparing Total Fertility Rate to Population Density as of 2023, in the U.N. World Population Prospects:

As you can see, high fertility countries tend to be lower-density (bottom right), whereas virtually all the countries with densities over 1,000 people per square kilometer have fertilities at or below 2. You might go on to look at data on regions within countries and conclude that high density leads to low fertility. That might lead you to two possible conclusions: 1) that population is thermostatic so that high TFR→high population→high density→low TFR→low population→low density→high TFR, and so on. Congrats, you have completed the homework assignment for the second week of a demographic methods class! You have not discovered some deep secret of the universe, trust me. 2) You might conclude that you should focus on building low-density housing developments waaaaay out in the exurbs.

But there’s a problem with this entire method. We don’t even need to consider those possible conclusions to see what the error is. Here I show the same graph with Italy (orange) and Nepal (light blue) blown up.

You can see that they have about the same densities, yet Nepal had a much higher fertility rate. That’s interesting!

So maybe Italian policymakers should go on trips to Nepal to learn what the Nepalis are doing to promote such high fertility! They are, after all, similar countries: similar population density, which Studies Show is closely related to fertility. Maybe Italy can learn something from Nepal!

But… can it really? I think most of us know the answer is “no.” There is no reason to expect that if Italy tried to “become more Nepali” that fertility would rise. More importantly, there’s no reason to believe Italy could “become more Nepali,” whatever that means. Italy can’t pass legislation declaring Italy 15% more Nepali. Even if Italy did try to legislate, say, a caste system or Hinduism or Buddhism, there’s no reason to think this would work. In fact, in Nepal, the caste system is legally abolished already: but socially still very much in force. And this might all fail anyways: maybe the secret to Nepal’s high fertility-for-density is actually its high elevation villages, or its prolific hydroelectric resources, or something about the cultural legacy of the Buddha.

Countries cannot choose to be other countries. They can only choose to be incrementally different versions of themselves.

The point I’m making is simple. Countries can’t jump across a cross-sectional graph. It’s not possible. Changes in a country occur iteratively, one at a time, while other things change at faster or slower rates, but the point is that the number of traits that vary between two countries is effectively infinite. And so we really learn almost nothing from cross-sectional variation.

No cross-sectional comparison of countries is never informative. This fact is so widely appreciated by demographers we have a fun pejorative for it:

“Reading history sideways.”

We teach our students: you can never do this. The progenitor of this notion is a demographer named Arland Thornton. He’s gonna come up a lot in this post. He’s got a very nice book called “Reading History Sideways: The Fallacy and Enduring Impact of the Developmental Paradigm on Family Life”. If you want to understand the world a lot better in one book, this book will help you do it. I don’t agree with everything in it, but the broad outlines, once you have them in your head, will scaffold all your other functional demographic reasoning.

The short version of Thornton’s thesis goes like this. Western man began to get an economic, political, and military edge on the wider world sometime after the Bubonic Plague. Also, Western man had been unusually isolated from the wider world for several hundred years in the early middle ages. Western man’s new encounter with “the world” arguably begins with the Crusades, but especially ramps up with the massive expansion of global trade in the 1400s. When Western man encounters the Americas and, within them, new peoples who seem to his eyes phenomenally backwards, Western man has to come up with an explanation, a typology, a story explaining Why The West Is Different. For centuries, Western man did not have such a story, except insofar as Western man was Christian man. But especially the encounter with Africa and the Americas forced Western man to explain what was economically, politically, demographically special about us.

When the West encountered the Rest and found them at a disadvantage, we came up with a story called “development.”

Development begins (explicitly, as Thornton shows) as a paradigm for explaining why Africans and indigenous peoples should be considered childlike, not mature, undeveloped, needing Western stewardship, instruction, leadership, domination. Over time the developmental paradigm mutates; by the mid-20th century, it is a story about the potential for uplift: if countries can “modernize,” adopt “modern institutions,” then they will “develop” (i.e. become healthier, wealthier, more prosperous). We’ll discuss that mutation later.

But think about how this story works. The West did not have data showing that any linear-like developmental progress existed. Most of Europe was barely removed in terms of civilizational scale and sophistication from the Roman period; much of Europe remained smaller scale and poorer than they had been in the classical epoch.

Before the developmental paradigm, the dominant Western paradigm had been cyclical: virtuous, strong, productive generations created complex and wealthy societies; wealth breeds indolence, sloth, and vice; vice leads to civilizational collapse. And so on.

The historic paradigm Western man held to before his encounter with Africa and the Americas in the 1400s and 1500s was basically cyclical, not developmental. The “idea of development,” the idea that societies are like humans who develop into “maturity” meaning wealth, complexity, etc, was invented in the early modern period. It came to be used to explain history, but especially to explain contemporary differences in societies. The industrial revolution really kickstarts this process even more. Here’s development words in English over time:

But the key point is, this theory was basically made up without any evidence. In fact the European experience to that point was cyclical, not developmental. Likewise, the indigenous experience in North America was not typified by “gradual but long-delayed or late-starting development.” The Maya had exploded to a massively sophisticated society and then collapsed centuries before Western man ever “discovered” the Americas. The largest urban agglomeration in North America (Cahokia) with tens of thousands of residents, massive monumental architecture, and trade stretching from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, collapsed under its own institutional failures centuries before Western man arrived. “Development” as such just was not a correct view of history, since history really was quite cyclical.

But Western elites had a sense of destiny. They guessed that they were special. And they were more-or-less correct: the industrial revolution vaulted Europe into truly special territory, economically, socially, demographically.

Two key points from this section:

Never read history sideways. Correspondingly, immediately downgrade your assessment of the credibility of analysts who present simple cross-sectional graphs to try to explain change over time. They are not thinking in an analytically sound way.

Europeans invented the idea of “development” to explain Africa and the Americas, and only belatedly actually managed to “develop” (i.e. escape prior economic peaks) much later with industrialization, a development not many of them ever anticipated.

2. Preferences Explain Everything

So we shouldn’t read history sideways. What, then, should we do?

The answer is, read it longitudinally. Across time. Our question should not be, “How do countries with more trait X vary on trait Y vs. countries with less trait X?” Instead we should ask, “What usually happens to Y in countries when X rises or falls?”

This is an actually useful question. If you can tell Italy, “When countries build more low-density settlements, TFR rises,” that is orders of magnitude more informative than, “Countries with more low-density settlements have higher TFR.” The first statement is informing policymakers about an actual potentiality; the second is asking Italy to become Nepal.

To do this, we need to forget our simple OLS regression model, and learn a modestly more sophisticated still-ultimately-OLS-based-but-with-fun-quirks model, a panel model with fixed effects. I won’t bore you with the math, but this model, common in economics and demography, basically looks within entities (countries, states, companies, whatever), and asks what happens within an entity when some variable changes. That’s exactly what we want! This method directly explores how we can explain predominantly incremental changes within mostly-static units.

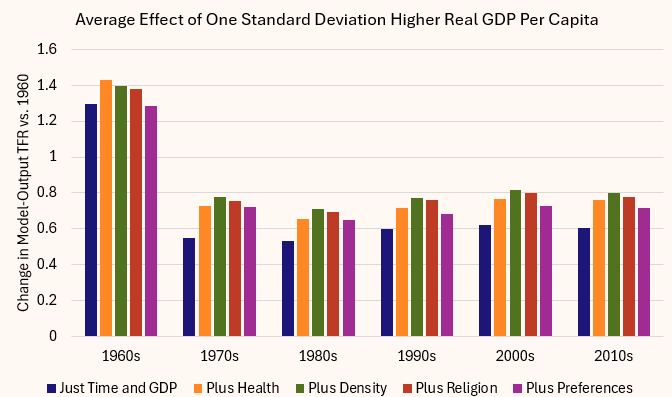

To understand how important this method switch is, let’s consider the case of GDP per capita and fertility. We’ll show the effect of 1 standard deviation change in logged inflation-adjusted GDP per capita on TFR across the decades of the 20th century, first using simple OLS, and second using a panel model with country fixed effects.

One standard deviation change in log real GDP per capita is associated with about 0.95 fewer children in the OLS model in the 1960s, and about 1.3-1.4 in the 2000s to 2020s. That’s a big decline!

In the panel model, the effects are much smaller: 0.2 in the 1960s to 0.6 after 2000. In other words, the OLS model overstates the effect of higher income by about 0.7-0.8 children. That’s a huge error! One standard deviation change in log real GDP per capita on average means about $10,000-$20,000 in higher GDP per capita. It matters a lot if that amount of economic growth reduces fertility by 0.4 children or 1.1 children!

Although higher fertility is correlated with lower income, fully 2/3 of the income effect evaporates when we simply look at within-country experiences with no other controls.

Reading history sideways would make you believe that “low fertility leads to economic growth.” Using longitudinal data would make you much more hesitant about that claim.

For interested readers, I have exhaustively debunked the supposed negative income-fertility link here, here, and here.

People have lots of hypotheses about what might cause falling fertility. Here are some popular theories:

“Fertility is falling because people are getting richer over time”

“Fertility is falling because of rising population density and urbanization”

“Fertility is falling because falling child mortality means people don’t need to have as many children to hit their family goals.”

“Fertility is falling because rising life expectancy means people have different ambitions/lengthened life strategies/changed saving requirements.”

“Fertility is falling because of falling religiosity”

We can examine these pretty straightforwardly. We’re going to use our panel model again. But now we’re going to add one more family of variable to explicitly control for time. We’ll use year fixed effects as well as linear time trends. Linear time trends are a variable for each country which removes their linear time trend across the dataset. If some country has constantly falling fertility regardless of other variables, well, that seems worth controlling for! Likewise if some country has constantly rising fertility regardless of other variables. We are also going to control for year fixed effects: if fertility falls everywhere in a given year (say, due to a pandemic), that seems like something we should control for! These basic time controls absorb a ton of variation across time. What they actually do is give us reasonable controls for “everything else.” Basically, these variables absorb anything time-correlated we might have forgotten to include (like background pace of technological innovation, or the expansion of contraception, or whatever other theory you want to advance). As you’ll see, none of this is going to matter, because we’re going to find some extremely compelling other variables accounting for tons of variation.

To start with, here’s the effect of income:

You can see the coefficients are positive. One standard deviation higher income (which means about $10-$20,000 more in real GDP per capita) means more babies.

I showed you above the basic panel implied more income means fewer babies. So what changed here? The answer is: time. It turns out, income is rising in most countries, and fertility is falling in most countries. These trends are occurring together but not necessarily the same.

The upshot is when I include controls for time, it turns out that “Periods of unusually fast economic growth are also periods of higher fertility,” or, to put the other way, “When economic times are unusually bad, fertility falls.”

That’s obvious when you put it that way! And yet, many people seriously argue that higher income is reducing fertility!

You can also see the income effect is fairly stable across time (except the 1960s), and also that adding more control variables does not have a big effect. Good economic times are good times for babymaking, and no variable you can chuck at the model is going to change that fact. If you want more reflection on this finding, see here.

Next, let’s consider the health variables: child mortality and life expectancy!

More child mortality is almost always connected to higher fertility. One standard deviation higher child mortality means about 80 more deaths under 5 per 1,000 births, so 8% higher odds your kid dies before age 5. Places with higher child mortality tend to have higher mortality for teens and young adults too; I would say this is basically telling us when a kid’s odds of dying are about 10-15 percentage points higher, people tend to have 0.6-1.4 more kids. Now, this is a case where causality could really run either way: maybe having more kids causes more kids to die! In practice though, decades of demographic research suggests that mortality replacement fertility is a real thing: when kids (or other family) die people have more kids to fill the gap.

Life expectancy, however, turns out to be a trivial effect. One standard deviation higher life expectancy (so 11 more years of life expectancy! that’s a lot!) actually yields more births, though very few more. This is counterintuitive. People often assume longer life expectancy will motivate a slower life strategy and fewer kids. But longer life expectancy also means women live longer, die of maternal causes less, and people are healthier, which could be pronatal. But ultimately you can see once we add in preferences that life expectancy has no effect at all. So this “slow life strategy” stuff is probably nonsense.

Here I also want to flag something important: those child mortality effects are statistically pretty robust. The standard errors are modestly sized, such that the error range across all 4 models never suggests a value less than 0.4 in the 99% confidence interval range. It’s very difficult to concoct a model where child mortality doesn’t look important. But for life expectancy, none of the models produce statistically significant (i.e. 95% confidence interval doesn’t overlap with zero) estimates.

Life expectancy beyond child mortality doesn’t seem to be a statistically robust predictor of fertility.

A similar story emerges for density.

You can see that an extra 200 people per square kilometer is pretty consistently associated with ~1.5 fewer children, a huge effect.

… but the 95% standard error is 1.7. Those “big” effects are statistically pretty trivial; lots of countries see their TFR rise when density rises, or fall when density falls. So density is a weak predictor.

Next up, let’s look at two variables related to values: the nonreligious share of the population and the average survey-reported desired number of children.

As you can see, one standard deviation change in the nonreligious population share (i.e. a 12 percentage point increase in unaffiliated) would actually… INCREASE fertility! Bizarre, right??? Here I will note two things: first, I’m using a restricted sample of only countries and years for which all data is available. When I drop that restriction and use all years for which religion data is available and reduce variable number, irreligion has the expected negative effect.

Second, the effect is not even remotely significant in this specification. Big changes in religion are associated with small and imprecise, non-robust increase in fertility. To me, that says “Religious unaffiliation isn’t actually very relevant for country-level fertility.” Maybe something like attendance frequency would matter more— but I’m limited to widely available international datasets, and attendance frequency is not available for lots of years and countries.

Finally, notice mean fertility preferences: about 0.2 extra kids for a 1 SD change in preferences (which is about 1.2 more desired kids). That effect is very significant, 99% confidence interval bottoms out at +0.06. So, when people want more kids, they have more kids. When they want fewer, they have fewer.

Now let’s take our “Plus preferences” final model and compare how all the estimates in that model shake out:

When we consider this model all together, we see several important facts:

Good economic growth is connected with higher, not lower fertility

Higher child mortality is associated with higher fertility

Higher fertility preferences are associated with higher fertility

Life expectancy, population density, and irreligion don’t seem like persuasive candidates for low fertility

To revisit:

“Fertility is falling because people are getting richer over time”“Fertility is falling because of rising population density and urbanization”“Fertility is falling because falling child mortality means people don’t need to have as many children to hit their family goals.”

“Fertility is falling because rising life expectancy means people have different ambitions/lengthened life strategies/changed saving requirements.”“Fertility is falling because of falling religiosity”

And one I didn’t tell you on the front-end:

“Fertility is falling because of cultural changes reducing desired family size.”

So, the best candidate explanations for falling fertility are basically, “Falling child mortality means people don’t need to have as many kids to hit their family goals, and those family goals are themselves simply falling over time.”

Now, it occurs to me, many people don’t have a good intuitive sense of how desired family size has actually changed over time. One reason for this is simply that there is no central database of survey data on fertility desires you can download and explore. I have been building such a database for several years now and am hopeful that 2025 will be the year in which it finally goes “live,” but as it happens I do have quite a lot of this data on hand. But because we don’t have survey data for all countries in all years, we have to make some assumptions. Specifically, we will make the assumption that changes over time in desired family size in countries for which we do have observations are more-or-less similar to the changes over time that occurred in countries and periods for which we do not have observations. As it happens, there are some fancy-but-boring mathy ways we can check this assumption, and it’s more-or-less true. Regardless, when we use this same assumption for both desired family size and actual fertility rates, we get the following estimates of global actual and desired fertility:

Both actual and desired fertility have fallen since 1960, but actual fertility has fallen much more. The biggest reason for this is actual fertility is also influenced by child mortality, which has fallen a lot since 1960.

Interestingly, desired fertility has fallen a lot less rapidly since the 1990s than it did between the 1960s and 1990s.

Actual birth rates have fallen by about 3 children per woman over the last 60 years, while desired family size has fallen by about 1.1 children per woman.

You will also notice that whereas in the 1960s humanity was, on average, considerably overshooting its fertility desires (probably partly due to a need to have “extra” kids to offset child mortality), today humanity appears to be appreciably undershooting our fertility desires. We’ll come to that issue in a bit.

(UPDATE: Since publishing, I noticed a recent paper which replicates and extends an old 1994 finding showing that within birth cohorts around the world, fertility preference data is an extremely strong predictor of completed fertility. So lest you thought this was just me spouting off, peer-reviewed academic research agrees with these extremely strong links!)

Three key points from this section:

A lot more kids survived. Families experienced a very real change in their family dynamics as the number of child burials plummeted, and the expected lifetime childrearing costs from a given pregnancy rose dramatically. When child death odds fall from 30% to 3%, the amount of time and money you expect to spend on a given child who is born is astronomically higher, and also the need for overshooting dissipates. Paradoxically, then, what happened to families was they didn’t “need” to have as many kids and they didn’t “want” to have as many kids, because the real price tag on kids goes up when kids survive more.

Even apart from child mortality-correlated effects, we know preferences declined on their own too from our panel model. This decline is what we want to explore more in the next section.

Today, fertility is actually lower than people report desiring on average around the world.

Now, this raises two huge follow-up questions:

Why is desired family size falling?

What about those many cases (especially rich countries) where people are having far fewer children than they report desiring?

3. Where Do (Preferences for) Babies Come From?

Let’s assume I’ve persuaded you that, globally, the big, world-historic story of falling fertility is basically just rising child survival and falling desired family size. Because this article is not covering the million possible counter-arguments, probably I actually have not persuaded you entirely of that. But supposing I have, we now have to ask why desires are falling.

And for that, we have to ask why people want things. Like, anything. Why is there a desire for something rather than not?

This question is not quite as simple as it sounds. Sure, people have some homeostatic needs and their brains are hardwired to give them powerful urges to acquire food and water and shelter and protection to ensure those needs are met. But the reality is today most people are vastly above these kinds of basic survival pressures even in rather poor countries. Furthermore, these base impulses don’t explain most actual preference variety: we find people in very similar subsistence environments with very similar genetic ancestries who have radically different preferences for pizza toppings or clothing styles or sex positions or whatever. It just isn’t true that some kind of widely shared underlying genetic architecture generates an extensive set of detailed preferences. Our genetic hardware gives us extremely vague suggestions and oblique, sometimes inexplicable-feeling nudges. It doesn’t actually do the work of setting tastes per se.

For that, you need culture. You like a specific wine both because your genes gave you certain tastebuds and neurons and also because your culture exposed you to certain experiences and wine options to frame your choice and inform your brain what the menu it could maximize on actually was. Maybe your inborn “nature” gives you a deep urge and desire to see punishment meted out to people who betray the group. In some societies, you will join lynch mobs hunting for witches. In others, you will do ritual dances against spirits. In others, you will play violent video games, or mob people on twitter, or start a nasty rumor about them at luncheon. If evolution provides us with a kind of schematic for human needs, our cultures provide almost infinite variation in how it gets filled in.

Cultures don’t all value the same things. Let’s ignore “world cultures” for now and stick with the original culture: the family.

Some parents go absolutely bonkers showering kids with praise for sporting achievements. Others give praise to kids for memorizing Torah. Others for sharing toys nicely on the playground. Others for just not throwing spaghetti at the wall at dinner this time. Some parents don’t praise their kids much at all! Even in cultures where we share almost all of our public myth and rhetoric, we end up inhabiting quite different cultures as children, because we had different parents. Some of us grew up in more or less violent or abusive cultures, others in rural woodsy ones, others barely saw their parents at all and were inculturated by friends or teachers or grandparents or whomever.

The point is, we learn culture, we learn it pretty young (though we continue to learn and test and modify it as adults), and these things we learn and internalize shape what we want.

Genes determine a lot of things. But cultural values have lower genetic heritability than almost any other trait, and we know that the reason kids have high likelihood of matching parent specific creeds and attitudes is because of cultural transmission, not because there’s some kind of gene for believing in the Virgin Birth.

We want things for lots of reasons. We want pleasures. We want to avoid pains. We want honors, and avoid shames. We want to be seen as good, worthy, prestigious; not as bad, unworthy, and detestable. We may vary in how we weigh this things: perhaps you long to walk to the guillotine greeted by cries of hate as part of your manifestation of the absurd in the world. Kind of an odd desire, but there’s no accounting for taste. Or, rather, there is an accounting for taste, it’s just a very granular accounting.

But perhaps the most common human desire is simply to feel good in comparison to other people you see as peers.

This good feeling may come from observing what food you get to eat. Or the house you get to live in. Or the clothes you wear. Or the God you worship. Or the enemies you defeat. Or the women you possess. Or the children you raise. Or the beating hearts of your foes you rip from their chests. Most of us want to feel like on whatever the yardstick of society is, we’re doing pretty good vs. other people like us. Humans are intuitive comparers, instinctual levelers. We want to know we’re not falling behind the group. Being hungry is bad, but it’s far worse to be hungry when you know other people have food. Humans routinely choose death before dishonor, or death before loss of love, or death before any number of other things. Humans routinely choose pain over shame: why do young boys play “pain games” and see who can eat the most chili peppers or do the salt-and-ice trick? Because the most powerful part of your usual, normal-circumstances brain circuitry is the interpersonal comparison function.

This desire is often shorthanded in online discussions as “status,” but that’s something of an incorrect label.

Most people actually do not want to max out the “status” scale. Most people are actually quite afraid of being at the top, of being a leader, of speaking publicly, of having to shoulder responsibility, etc. Being the main character risks you getting made into the main character. Most people are not instinctual leaders, because leadership is extremely socially (evolutionarily!) costly. The reality is most people aren’t looking to maximize status, and in fact there are strong evolutionary reasons to suppose that humans actually developed with psychological mechanisms to pretty actively restrain this kind of maximalist status seeking. Humans don’t have nearly as intense of alpha-competitions as many herd and pack animals. Other primates mostly don’t either. Very few human societies in existence have ever had those kinds of dynamics. Most of us experience almost instinctual disgust and a desire to undercut people who seem to be too-openly putting themselves at the top of the pecking order without just cause.

What people want is not to maximize status, but to avoid the very high psychological, social, and material cost of being made to feel inferior, subordinate, or part of the out-group.

The goal for most people isn’t to be at the top. It’s to stay away from any risk of being anywhere near the bottom. To be comfortable. To be doing fine. The objective is to say “We’re doing all right” and to mean it.

4. Putting It All Together: Developmental Idealism

Now, let’s return to Arland Thornton. He argued (I think correctly) that “development” didn’t stop as an intellectual paradigm for Westerners to explain the world. He argues that “development” became an “ideal” for much of the world, and in particular that a specific set of ideas about sex and family became inextricably tied to “development.”

Development became an ideal because the social worlds of people in poor countries expanded to make them aware of European wealth, and suddenly they found themselves “at the bottom” of a brand-new social scale. That feels horrible.

Again, I’m skipping over a lot of interesting details, but basically, imagine you are encountering Western man for the first time. Much about him is unimpressive. Indigenous peoples routinely left us extensive records attesting to their view that Western culture actually super sucked. They regarded Western man (and especially western woman!) as less free and in many ways less prosperous than themselves. Whereas Western man came up with a story of “development,” the “undeveloped” peoples he looked down on actually found his culture generally not worth emulating. Conversions to Christianity were not especially rapid, and where they were rapid occurred either by force (so sort of an exception that proves the rule) or among missionaries who essentially nativized and indigenized the faith and removed it from the trappings of Western hierarchical society. Time and again, whereas indigenous people came to admire and desire the productivity of Western industry, our wealth and power, and they were happy to buy our products, they rarely fell in love with our culture.

And yet around the world today, everybody is obviously becoming Westernized. Even though everywhere you go, people complain about Westernization and openly remark on how bad a lot of the vices of Western culture are! What’s going on??

Thornton’s thesis, which I endorse, is that basically there was a bait and switch.

Western man was able to convince the world that if you want to be wealthy, you’ve got to be Western(ized).

There were areas where this was approximately true. It’s hard to build a wealthy society without formal property rights, courts, the rule of law, some degree of state capacity, etc. Western ideas about scientific culture also proved to be invaluable. So the argument that “Adopting prototypically Western attitudes, beliefs, values, and institutions will make your society much wealthier in the long run” was not entirely false! “Don’t marry your cousin and don’t do honor killings” was actually incredibly good advice from the West!

Here’s a shorthand version of the “Developmental Idealism” cycle of social change:

Europe gains a big economic lead

Europe expands outwards to encounter the Rest

a. Europeans adopt a story of development as opposed to cyclicality

b. Even as the Rest gradually or quickly realize that they are at the bottom of a new social pecking order

a. Europeans promote a story whereby they are developed because of their culture (including their family culture)

b. The Rest realize that it’s impossible to just rapidly, directly “adopt” Western wealth; capital formation and tech transfer is slow and hard. But you can adopt Western cultural forms at a low cost.

The Rest adopt Western cultural forms regardless of if they actually get rich

This story is correct. How do we know it’s correct? Because we know that modern fertility decline began in France (and to a lesser extent Massachusetts), metastatized in England, and spread exactly as you’d predict and linguistic ties to France and industrial connection to England. We know that when countries have more NGO, diplomatic, and media ties, their fertility converges towards the wealthier end of the bilateral. We know that villages that randomly happen to have better radio and TV service or early internet connectivity end up adopting Western small-family sizes faster and earlier. I could go on. The TL;DR is simply that we know from numerous studies that:

Fertility behaviors change if and when Western CULTURE arrives, which is sometimes before and sometimes after when societies actually experience economic growth, if they ever do.

Earlier I compared Nepal and Italy. Now let’s compare Nepal and France.

Do you know what Nepal and France have in common?

They have the same fertility rate (~1.8).

Puerto Rico and Singapore have the same TFR. Finland and Costa Rica. Albania and Canada. Brazil, Iran, Azerbaijan, Australia, the US, Kosovo all have roughly the same. India and Utah.

I could go on. The point is, fertility is falling everywhere. Don’t believe me? Here’s average TFR by decade for countries, grouped by their inflation-adjusted income level:

In the 1960s, countries with real GDP per capita under $5,000/yr averaged a TFR of over 6 children per woman. Today, they average under 3.5.

Fertility has declined within income levels!

So the basic synopsis of why people (stopped) wanting babies is:

Western countries (explicitly and implicitly) promoted their idiosyncratic small-family-size norms. These norms were not necessarily actually that appealing in and of themselves at first, and were usually resisted (India still has arranged marriages today!). But as Western countries opened up an increasingly yawning gap between themselves and the rest of the world in terms of productive capacity and standard of living, the rest of the world didn’t feel very good about it. They were aware (thanks to improved transportation, communications, media, trade, etc) of the Western advantage, and awareness created a not very nice feeling that they weren’t doing okay.

Often this not-very-nice-feeling came from war. Countries would lose a war against a colonial or imperial power, and it would be a wakeup call about how massively dominant Europe had become. But sometimes it came without war. Regardless, some forward-looking non-Western elites would sometimes try to “Westernize” or “modernize” their communities to compete more. Prototypical cases would be individuals like Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, or Sequoyah for the Cherokee.

Regardless of how it happened, two facts have become more and more true: 1) many people started to feel not good about how far “behind” how “undeveloped” their communities were and 2) it was much easier to adopt some pieces of Western culture (like small family size) than others (like inclusive political institutions, independent police forces, rule of law, democracy, or property rights). Now, I do have to note: this was partly because Western states often sabotaged the actually-useful stuff. Where the British ruled directly (Singapore, for example, or Hong Kong) they did create British institutions. But where they ruled very indirectly (Sierra Leone, for example, or Nigeria) they often actively propped up ineffective, divisive, and extractive institutions. Most colonial empires governed most of their territories with very small colonial elites, and relied on indirect control by clientelized local extractive elites. As a result, colonialism often prevented the emergence of some useful “Western” institutions.

Regardless, things like small family size could be adopted, and Western governments enthusiastically promoted them. They made no effort to support indigenous population growth (lolololol), and in the 20th century shifted to active antinatalism. The emergence of neo-Malthusian fears like the “Population Bomb” myth also fed this process, but did not begin it.

This thesis also tidily explains the social function of anti-colonial literature, anti-Western terrorism like Boko Haram, and the success of Indian Hindutva today, as well as the resurgence of interest in traditional Chinese culture in China. The “development” process is first and foremost cultural. Westerners get confused why Boko Haram opposes “development,” and it’s actually not first and foremost because Nigerian Muslims just loooooove child mortality. It’s because they mostly experience development as cultural threat.

The developmental idealism paradigm provokes some in a low-income society to proactively Westernize: become Western to get the prosperity. But it also triggers conservative reaction: radical defenses of traditional society. Thus, the development process recapitulates through its culture-first approach something like the left-right divides of Western society.

As a result, billions of people sincerely believe the lie that if they and their country(wo)men could just stop having so many babies, then they could be rich.

Why do I say billions? Here, you can find a long list of papers surveying attitudes related to “developmental idealism” in countries around the world. Poor countries routinely turn up majorities of their country agreeing with statements like “If fewer parents choose marriage partners for their children this will help the Malawi nation to become richer.” People in poor countries earnestly think, have genuinely been so massively deceived by Western success, that if they just arrange their sex lives like Europeans do, they’ll get rich, even though this just isn’t at all true.

Thus, when we think about falling fertility globally we should basically be thinking about peoples’ developmental aspirations, and the causal reasonings they make about how to achieve a reasonably good life in comparison to peers.

If we expand their peer pool (such as with social media), that’s going to influence their sense of where they stand on the ladder of success. Mostly negatively. Which means they’ll look for ways to climb, and developmental idealism promotes the notion that the way for a society to climb is… to not have babies.

5. Fertility Below Desires: Coordination Problems

So far, I’ve explained two fundamental, big factors driving falling fertility: declining child mortality, and declining desired family size likely motivated by developmental idealism.

But astute readers will balk at the idea that Finland, which has had an extremely rapid fertility decline since 2010, had some sudden surge in developmental idealism. I have argued elsewhere that a change in attitudes towards work probably is part of the problem, but it’s not the whole story.

Let’s take an interesting case of a country with rapidly falling fertility: Turkey. As recently as 2017, Turkey’s total fertility rate was 2.08, at or around “replacement rate.” It had been stable at about that level from 2009 to 2017. Then, it started falling.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Lyman Stone to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.