Humans Are Genetic Monogamists

Ethnographically, demographically, genetically, if you adopt polygyny, you're gonna lose

Recently,

ran a post by which claims :Polygamy is a natural attractor state for humans, since it satisfies the desires of powerful men to have multiple wives and the desires of women to have elite husbands. Monogamy requires both elite men and many women to sacrifice their desires. In exchange, it provides strong checks on negative-sum intrasexual competition. Powerful married men are not constantly on the lookout for another wife and can devote their efforts to other pursuits, while less powerful men, who would be shut out of marriage in a polygamous society, have fewer evolutionary incentives to stab their compatriots in the back. The result is a much more cohesive and powerful society.

This went a bit viral when

shared it on Twitter.I’m not gonna tackle the whole post, and I don’t even necessarily disagree with it. Rather, I want to use this as an excuse to explore one of the most interesting and common errors people make about the human past:

People wrongly believe ancient humans were polygamists.

I’m going to convince you that monogamy has always been the dominant human norm, and that in fact we are evolved for it. I’m gonna do this several ways:

1. Genetic data on human reproducing chromosomal lineages shows that the rise of polygyny is genetically recent, not ancient or primordial.

2. To the extent polygyny has a typical civilizational stage associated with it, it’s pastoralism, not hunter-gathering or settled agriculture.

3. The ethnographic record of traditional and foraging societies shows that polygyny is almost never the dominant marriage form even where it is practiced.

4. Modern demographic data shows polygyny is not the dominant marriage form even where it is practiced.

5. Human anatomical and population-genetic traits are not supportive of a deep history of polygyny.

6. It’s actually clear idiosyncratic norms in specific cultures actually drive episodes of polygyny.

7. Polygyny is maladaptive and struggles to persist.

1. Genetic data on human reproducing chromosomal lineages shows that the rise of polygyny is genetically recent, not ancient or primordial.

One of the coolest things happening right now is that more and more ancient and modern DNA is being sequenced. This allows us to get a sense of when and how human genes changed. But it also tells us something else very cool: about how many Y chromosomal groups were breeding and leaving descendants a given number of human generations about, and also about how many mitochondrial DNA groups were doing so? Basically, men and women. One recent paper did this. A similar approach can tell us about the average age of parents at which children were born over deep human history, and one recent paper has done this work. I’ve converted their findings into the graph lines shown here:

About 150,000 years ago, humans lived in a variety of forager societies. They used a range of very simple stone tools and probably mostly had socially monogamous unions.

We know these unions were socially monogamous because there were only about three mtDNA lines per Y chromosomal lines, which is about the same observed in modern genetic samples.

This is also consistent with social monogamy alongside younger female parentage, male remarriage after spousal death, high maternal mortality, and periodic adultery or rape. “Social monogamy,” i.e. the vast majority of men were basically partnered with just one woman at a time in terms of socially licit regular pairings, was probably the dominant mode of human reproduction for about 100,000 years or so.

While seasonal or temporary gatherings of large numbers of human foragers were probably very common, it’s likely most time was spent in modestly size kinship-based groups. And in that context, the typical child’s mother was about 22 years old at birth, while their father was about 29. Likely half of the children born to these couples died before puberty, and many mothers probably died too. The fact that the age gap was wider than in modern societies does suggest that a lot of women died young from childbirth and that a lot of men remarried.

But over time, and especially between 70,000 BC and 40,000 BC, female and especially male ages at birth rose even more. By 40,000 BC, as anatomically modern humans were starting to leave Africa in large numbers, the average father was about 34 years old, while the average mother was about 24. Thus, even before humans left Africa in large numbers, we were already experiencing meaningful change in demographic behaviors: age at reproduction was rising. This could mean age at first birth was rising due to postponement, or it could mean that humans were having babies until later in life. This is hugely important to grasp: a thousands-of-years-long trend in rising age at birth existed among hunter-gatherer societies in Africa. There were social trends before the end of the last ice age and before the emergence human civilization, not simply hundreds of thousands of years of stability. My aim here is to emphasize that not only did primordial human societies have a lot of variation in different areas, but also varied a lot over time long before agriculture, urbanization, or the dawn of “history.” There may have been huge waves of shifting social and cultural values about which we know nothing.

But then, suddenly, and especially after about 20,000 BC when the ice sheet covering much of Europe and North America was beginning to recede, age at reproduction plummeted. This period is associated with the emergence of new cultures that buried some of their dead in ritualized and decorative ways, invented and used ceramics and pottery, developed improved weapons and hunting techniques, and left behind art loaded with a large number of figurines of fairly rotund women. We know of these cultural changes because they are recent enough and happened in countries with big enough archaeological budgets for us to find a lot of evidence of them: but changes 80,000 years ago might have been just as dramatic, simply leaving less evidence. By 0 AD, average age at birth had fallen back down to 22 for women, and to just 26 for men. For reference, the very earliest indicators of proto-agriculture in human society are from 18,000 BC or so, a bit too late to have been the initial cause of the cultural change. And in fact, agriculture in the sense of people living in the same area and intentionally planting and harvesting crops would not begin until around 13,000 BC to 5,000 BC in various parts of the world.

Turning to the other line on the graph, we can ask how the ratio of breeding men to breeding women changed over time. Falling from around 2.5 reproducing women per reproducing man in 150,000 BC to about 1.5 in 60,000 BC, the ratio jumped up to about 3 women per man between 60,000 BC and 25,000 BC. That’s when age at birth was rising too. So that’s consistent with a story where perhaps as humans were leaving Africa, some polygyny emerged, or perhaps something like serialized polygyny. Serialized polygyny would also explain older maternal ages as it tends to increase birth spacing for women. Serialized polygyny tends to be associated with rather low female completed fertility, which should suppress population growth rates. There is indeed a population bottleneck around this period, perhaps suggesting humans left Africa, adopted serialized polygyny, and this resulted in lower population growth for a period of time.

But after 20,000 BC, just as age at parentage was falling, the ratio of mtDNA to Y lines skyrocketed to unprecedented heights, perhaps as much as 10-16 reproducing women per reproducing man in about 5000-4000 BC, before falling again in the historic period since 4000 BC.

These numbers bear some interpretation. First, as I noted above, 2.5 women per man does not imply widespread polygamy. This same genetic approach implies between 1.5 and 4 breeding women per breeding man today, in a world where monogamy is overwhelmingly socially normative for most of humanity, and so we can confidently rule out the idea that primordial humans were habitual polygamists.

On the other hand, a ratio of 6 or 8 or 12 reproductive women per reproductive man, as was the case between 20,000 BC and 0 AD, almost certainly indicates widespread polygamy and, in particular, large numbers of men having few or no descendants because they never had a pair-bonded partner with whom to reproduce.

Second, these figures refer to reproductive men and women who left genetic traces in more recently documented populations. It’s possible that some historic Y-chromosome lineages (that is to say, men) and perhaps also mitochondrial lineages (i.e. women) may have vanished from modern populations. It certainly is not the case that the raw number of men compared to women plummeted; just some groups of men didn’t leave their genetic markers in populations we have been able to genetically sequence in recent decades. Such genetic ghost populations are known to exist in at least a few cases: at least one such African genetic ghost population exists, a once large group which today has no descendants; furthermore, there was at least one very early (what archaeologists call pre “Clovis”) cultural group in the Americas which today has left almost no descendants except for a small genetic signature in some central Amazonian populations. It is possible the period between 30,000 BC and 4,000 BC saw a considerable number of Y-chromosome (male) population groups eliminated from the human genetic record.

What we absolutely do know is that a small number of Y chromosomes had gobsmacking numbers of babies, as another paper shows:

There’s one case of a massively productive Y-chromosomal lineage in about 13,000 BC associated with the small number of Y chromosomal lineages that migrated to the Americas and became totally divergent after, but between 6,000 BC and 4,000 BC, there are a lot of these lineages in the “Old World.” The first are in East and South Asia, then in Europe, then again in South Asia, then in Africa. So this explosive lineage variation is an “out of Africa” thing. It occurs well after agriculture is developed. It seems to occur around the time of the earliest proto-states, which we believe is also when pastoralists got really good at their own subsistence style. Interestingly, these lineage explosions almost all predate horse domestication.

2. To the extent polygyny has a typical civilizational stage associated with it, it’s pastoralism, not hunter-gathering or settled agriculture.

And as it happens, these “young lineages” predominate in the genomes of pastoralists.

In the common just-so story of deep human history, polygyny is a feature of highly unequal, settled societies. But in the actual genetic record, it’s actually pastoralists and nomads who show the most polygyny!

Perhaps greater agricultural surplus enabled some inequalities to develop in sedentary societies, and those inequalities translated into some people and groups dominating others, with the practical result of being on the losing end of this process was that men tended to be killed and women enslaved. Women’s (mitochondrial) DNA was preserved, but men’s (Y-chromosomal) DNA was not. There’s definitely some truth to this story: historic and ethnographic accounts of early agriculturalist societies point to some elite men (like kings) having hundreds of children from many women.

But even as some agricultural societies did become highly unequal, others didn’t. The evidence from the Harappan civilization of the Indus river valley in modern-day Pakistan and India suggests they were a sophisticated, urban, agricultural society with advanced craft production, long-distance trade, and organized warfare: but very little visible evidence of dramatic social inequality. One of the earliest agricultural societies and one of the earliest urban societies therefore dramatically contradicts the standard story. Doubtless some kind of inequality existed among the Harappans; we needn’t idealize them, but it just isn’t the case that as soon as humans learn to store seeds they inevitably start creating extractive hierarchies.

Nor is it actually the case that foraging societies are necessarily egalitarian. We’ve already seen evidence of this: status is equally predictive of male reproductive success in foraging and agriculturalist societies! A further example may drive home the point: before European colonization, the fishing societies who lived in modern-day Oregon and Washington had enormous differences in quality of life associated with social status, such that elites in those societies literally doused themselves in fatty oils and celebrated sumptuously excessive feasts—which sometimes included ritual cannibalism of their slaves. Those slaves amounted to perhaps as much as 25% of the total population. On the other hand, their close neighbors in northern California didn’t have slavery, but did have a developed money-based commercial economy which also had its own kind of dramatic class differences, and indeed money inequality led directly in these societies to unequal access to wives.

Massive inequalities existed without what we might think of as conventional agriculture.

Certainly foragers probably had some practical factors that militated against the emergence of powerful hereditary property holders in many cases, and the rise of agriculture may have made the emergence of some kinds of hierarchical domination more likely, but the idea of primordial humans as reflexive egalitarians and early agriculturalists as nascent totalitarians has no basis in theory or evidence.

Moreover, the rise in the mtDNA/Y Chromosome ratio shown above begins long before and continues long after agriculture was already widespread. The same research described above in reference to age at birth analyzes the data by region and shows that lopsided mating ratios persist well into historic periods. Moreover, the dramatic decline in men’s age at birth is not consistent with a story whereby long-term wealth accumulation from agriculture gives rise to wealthy elites:

The men reproducing with large numbers of women were getting younger and younger over time, not older and older, suggesting that the sexual and reproductive benefits from status accumulated over a long period of accumulation were falling, rather than rising.

Other evidence also complicates the link between agriculture and the shrinking number of reproducing men. For example, evidence for rising polygyny in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East points to a major increase beginning around 18,000 BC: yet wheat and barley would not be domesticated until 13,000 BC at the very earliest. Rising polygamy rates occurred almost 5,000 years before crop domestication. The absolute oldest quasi-urban sites ever excavated, like Natufian structures at Jericho or a site called Catalhuyuk in Turkey, date from 10,000 BC to 8,000 BC: fully 8,000 years after the rise of polygamy and about contemporaneous with grain domestication. In other words, polygamy began to rise before the invention of agriculture, not during or after. Rising polygamy was part of the cultural package that gave rise to agriculture rather than simply a product of greater surplus.

It also isn’t the case that the male-female reproductive number ratios are the most lopsided in the most intensively agricultural regions. Some regions of the world around 20,000-4,000 BC were more specialized in crop production, but others adopted more pastoralist lifestyles, herding animals across grasslands and hills. While pastoralism and agriculture existed side-by-side in all regions and many people practiced some of both, in Siberia and Central Asia pastoralist lifestyles were particularly dominant on the wide Eurasian steppe. Strikingly, these steppe lands also had far higher ratios of reproducing women to reproducing men. It is on the Neolithic steppe that the most lopsided breeding ratios emerge. In 10,000 BC, the ratio of reproducing Y chromosomes to mtDNA lineages was 22% higher in Central Asia than the Near East.

In other words, it wasn’t just the fully sedentary groups that saw an explosion of elite male reproduction. It was also, and in fact especially, the pastoralist communities of shepherds and herders of the steppe. In more recent periods, historic genetic research has identified this region of the world as repeatedly producing “star pattern” lineages, meaning a single Y chromosome associated with a large number of mtDNA lineages: clear signs of elite male polygamy.

The idea that it might have been the pastoralist steppelands driving unequal reproduction among men should not be historically surprising. This is the same region which produced peoples who repeatedly exploded into the sedentary societies of Europe, India, the Near East, and China. Lopsided sexual access was not most strongly associated with, say, the Sumerians or Babylonians or European Neolithic Farmers—it is most associated with the pastoralists and steppe peoples after 20,000 BC, whose descendants thousands of years later would be archaeologically-identified groups like the Yamnaya or Corded Ware Culture, or, more familiarly, “barbarians” like the Scythians, Huns, or Mongols. We’ll talk more about these groups later, but it is not a coincidence that the most prodigiously reproductive human in recorded history is Genghis Khan, ruler of a steppe empire: 8% of all men within the former Mongol Empire are direct patrilineal descendants of Genghis Khan! That’s insane! Dude must have had gajillions of sons!

The extraordinary mobility of steppe pastoralists afforded their elites remarkable military advantages: mobility made it easier to take resources from sedentary societies (especially women as slaves) and harder for the sedentary societies to strike back. Shepherd-raiders could move their flocks, but farmers were tied to their farms. Furthermore, mobility meant that men might spend extraordinary amounts of time far from pair-bonded mates if any existed, weakening the exclusivity of those bonds. Pastoralism enabled these groups to move around with the speed of foragers, but to have nutrition and population scale somewhat similar to settled agriculturalists. This also explains why the male age at birth fell so much:

Instead of long-accrued social status or stored wealth driving reproductive success, warlike young men raiding farms to haul off portable wealth, food, and slaves became a dominant part of human reproduction.

But over time, settled agricultural societies nonetheless saw faster population growth.

They built cities, innovated new technologies (though pastoralists kept up on that front, such as by domesticating the horse or building chariots), and their superior ability to convert land into calories made the settled peoples demographically overwhelming. It took time for agriculture to fuel this demographic advantage, and so it was not until after around 4,000 BC that agricultural societies had reached enough scale and sophistication that quasi-states could begin to emerge and, as they emerged, create territories and cities often (but certainly not always) sheltered from pastoralist predation.

The most plausible story, therefore, is not that settled agriculture led to hoarded surplus wealth creating highly reproductive elites. While that dynamic absolutely did happen in many sedentary societies, the actual forces driving truly epochal imbalances in male reproductive inequality were the superior mobility of pastoralist peoples which gave them greater power to strike at agriculturalists and limited agriculturalists’ ability to strike back. The emergence of oath-bound warrior elites whose moral norms were totally divorced from the ancestral human mating environment helped too. The fact that, for example, the Yamnaya people of the Eurasian steppe created intense warrior elites gave cultural license to a material advantage. Subsistence modes might make it easier or more comfortable for societies to make certain social and cultural choices, but they remain choices. Even as agriculturalist societies grew, pastoralist cultures kept up the pressure through the domestication of the horse, perfection of chariot warfare and archery, and the invention of the stirrup, funneling successive waves of conquerors down the international highway of the steppe until the 1400s AD. Settled societies do not mince words in the historic record when discussing their fear of these groups, and the genetic evidence makes it crystal clear that those fears were entirely reasonable. Because these rapacious pastoralist warriors were only too happy to forego pairbonded monogamous mating and use violence to gain access to huge numbers of sexually non-free women, a huge number of males in pillaged societies vanished from the genetic record, and we do not know what share of them were killed, enslaved, or fled into a lonely existence.

This story has the added benefit of being most consistent with the archaeological record of violence. When archaeologists excavate bodies, it’s often possible to tell if they experienced violent injuries. Combining together data from thousands of historically excavated bodies, archaeologists recently found that violent death rates in the Mesolithic and neolithic periods, when agriculture was first emerging, were not very high in historic comparison: about 5% of recorded deaths. Violence spiked in the Chalcolithic period before falling in the Bronze Age, only to rise again with the Iron Age. The agricultural revolution in the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods simply was not associated with an inordinately large amount of violence: but the Chalcolithic period (for that study defined as 4500-3300 BC) was uniquely violent, and that period is right when a major wave of violent raids and migrations from the Eurasian steppe into Europe and the near east was beginning. Even today, pastoralist groups (and ethnic groups with more recent history of being pastoralist) have higher rates of violence within modern countries.

3. The ethnographic record of traditional and foraging societies shows that polygyny is almost never the dominant marriage form even where it is practiced.

We have a lot of data about traditional societies and foraging societies. I really like

‘s work on this. You can read lots of it here, here, or, the specific summary I’m gonna talk about, this tweet right here:This is showing us, using what’s called the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample, which is a careful ethnography of tons of societies, the share of wives who are in polygynous marriage. This is actually stacking the deck in favor of polygyny, since if we did the share of husbands in polygynous marriages it would obviously be tons lower, since some husbands have many wives: polygynous marriages get counted multiple times on the wife side, but once on the husband side. So this tells us the share of wives who are polygynously wed, but the share of husbands is definitely lower, and FWIW since most societies are patriarchal, I think we can assume that “Norms among men” are actually what is going to define the culture more than “Norms among women but largely set by men.”

What you can see is that some nontrivial polygyny occurs at all subsistence modes. But it’s highest for horticultural and pastoralist societies. I don’t belabor too much the horticultural side, but notice that, despite wide standard errors, the polygyny share goes up from foraging to pastoralism, but way down for agriculture.

This strongly confirms the section above that polygyny is not a common feature of agricultural societies, and is more typical of pastoralism.

But notice the percents!

Even the top of the standard error bars doesn’t reach 50%!

There are almost no ethnographically documented societies where a majority of wives are in polygynous unions.

This just is not a thing that happens often.

Humans are social monogamists!

4. Modern demographic data shows polygyny is not the dominant marriage form even where it is practiced.

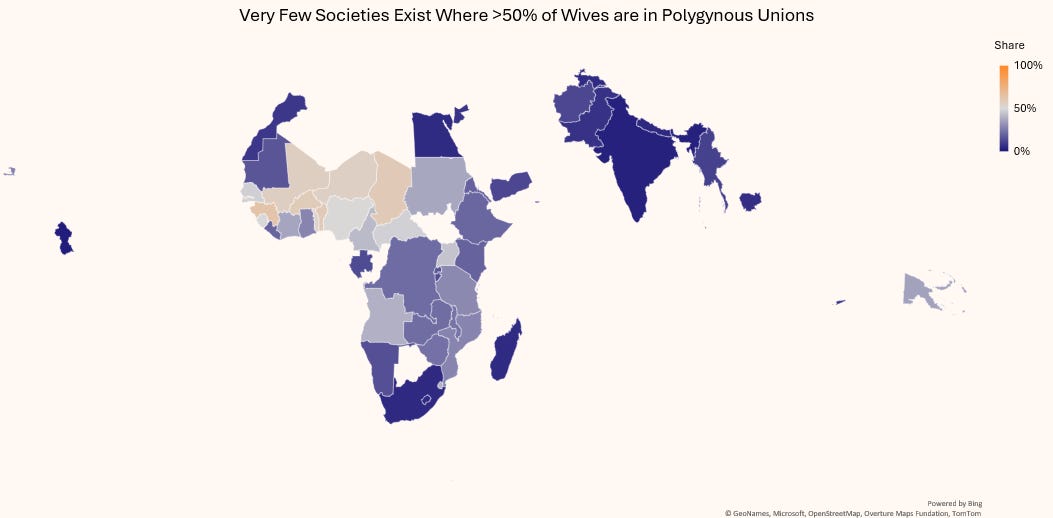

In some countries today, polygyny still exists. In many of those countries, we actually have data on how common it is! So, here’s the share of wives who are in polygynous unions, in surveys 2002-2022, using the most recent survey available (DHS or AIS) for each country:

Blue means “less than 50%” and orange means “more than 50%.”

There is a band of countries around the Sahel with slightly over 50% of wives in polygynous unions.

What do these areas have in common?

For the most part, they are almost all areas with recent or current pastoralism as a major mode of production, and also they are almost Islamic areas.

So here we find that 1) “Extreme” polygyny remains strongly connected to pastoralism, 2) In most societies with polygyny, polygyny isn’t dominant (even if I limit to societies where 5%+ of wives report co-wives, the mean wife-in-polygyny-share is 34%, suggesting most wives are monogamous!), 3) Maybe Islam matters too?

Even in modern societies that accept polygynous marriage, polygyny is not the dominant marriage form.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Lyman Stone to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.