Is There a Huge Increase In Women Wanting to be Childless?

No, but a bunch of public surveys did have their methods go to crap after COVID

Recently on their podcast, Simone and Malcolm Collins reviewed a bunch of data on desired childlessness. Specifically, they cited some recent surveys claiming that perhaps 30-60% of young women today desire to be childless, vs. 5% in past cohorts. This sounds like a dramatic change, so I figured I’d look into it and see what the numbers look like in long-running surveys. I won’t specifically go through their podcast, but instead am just using it as a jumping-off point to go through some recent fertility preference data. Here’s what we’re gonna find:

The National Survey of Family Growth shows a recent decrease in fertility intentions and wants (but it’s all about method changes)

The General Social Survey and Gallup show stability or increase in fertility ideals

Monitoring the Future shows a decline in fertility ideals of high schoolers (but it’s all about method changes)

The Demographic Intelligence Family Survey is a very accurate private survey alternative and also shows us people have weird preferences

The last two sections will be paywalled, sorry!

But before you go, some scheduling reminders:

I’m in San Francisco March 9-12 with some schedule slots open! Let’s meet up! DM me if you want to get coffee.

I’m in Salt Lake City March 12-13! Let’s meet up!

I’m in Austin March 27-29! Let’s meet up, or, come see me speak at the Natalism Conference! Use promocode “Lyman” for a $100 discount on registration.

The National Survey of Family Growth shows a recent decrease in fertility intentions and wants (but it’s all about method changes)

Since the 1950s, the U.S. government has been running a semi-regular survey of family growth. First it was the Growth of American Families Survey, then the National Fertility Survey, then since the late 1970s the National Survey of Family Growth. Since 1995, it has had more-or-less its modern form. I’m going to use data since 1988 to explore preferences (the pre-1988 sample had some quirks which make it not quite as relevant).

The NSFG explores fertility preferences in three ways:

Asking women if they want any more children at all

IF YES: asking them if they (and/or their spouse) actually intend to have any more children at all

IF YES: how many more?

Adding the numbers from #3 to current pregnancies and prior births can tell us women’s intended family sizes over time.

Intended family size is not a measure of what women WANT: it’s a measure of what women want AND THINK IS POSSIBLE.

So we shouldn’t see intentions as representing “desires.” They’re desires conditional on a range of practical judgments. If family life is getting much harder, intentions could decline even if underlying intensity of desires is totally stable.

Here’s what intentions look like for women 15-49:

As you can see, TFR has always undershot intentions, but the extent of undershooting varies. In 1988, the gap was small. In 1995, the gap was big. The gap shrank through the late 2000s, then grew after 2008 or so. Between 2017-19 and 2022-23, the gap shrank again as intentions fell off a cliff. By 2022-2023, the average American woman reported about 1.7-1.8 children in her intended family, the lowest level on record.

So we can see a big decline in intended total family size between 2017-19 and 2022-23, and more gradually between 2010 and 2017-19.

But notice that fertility declines first. Now remember how intentions are calculated. We ask women “Do you want any more?” then “And actually intend?” then “How many?” and we add it to prior parity. If TFR is falling, the distribution of prior parities will fall correspondingly, and so intentions will be dragged down when fertility falls. And you can see this visually! Intentions decline after the big fertility decline sets in.

It’s not that women started having fewer because they intended fewer; they started intending fewer because they had fewer.

Now, more complicatedly, we can also synthetically estimate something like “projected intended family size” and “projected wanted family size” through a more convoluted calculation. For this approach, we take the odds that childless women intend to have 1 more, the odds women with 1 intend to have 1 more, the odds women with 2 intend to have 1 more, etc, etc. We then essentially attrite a synthetic population through the parities. We weight this by the observed parity distribution, and this tells us, “If every woman who intends to have an extra child has it, and then her odds of intending to have another child after that are identical to women currently at that parity, and so on across all parities, how many children would the average woman have?”

We can do these for the “Do you intend any more?” and the “Do you want any more?” questions. If women say “I don’t know” or refuse to answer or say something like, “If God gives it to me,” we code them as “Do not intend any more” or “Do not want any more.” This is a debatable assumption, but it steelmans our argument.

We are going to assess these intentions in two ways. First, we will just take the simple cohort implications for all periods. Then, we will re-run the calculations, but we will chain the underlying parity distribution to its 2007 levels, to figure out “How much change in intended family size is caused by a shift in the underlying parity distribution?” vs. “How much change in intended family size is caused by a shift in parity-progression intentions?” i.e. propensity to desire more.

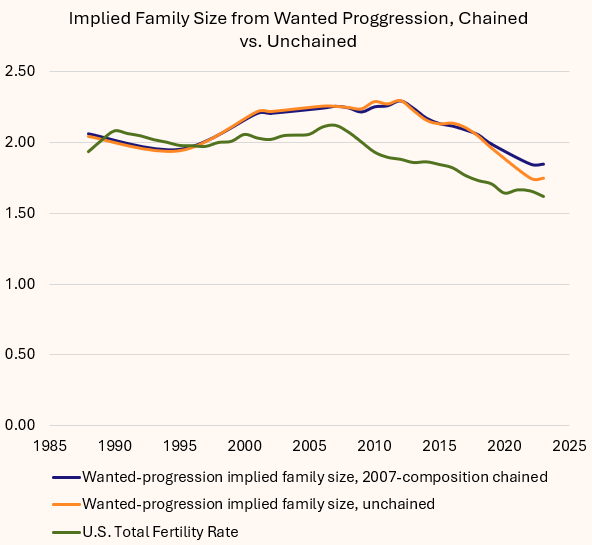

Here’s the result:

Looking at implied family size from wanted progression, we see that chaining to 2007 parity mix had basically no effect on estimates 1988-2017. From 1988-1995, actual fertility rates were very close to the family sizes implied by wanted parity progression. Gaps got huge around 2008-2017. Then wants have plummeted since 2017-19.

But look at the decomposition: for whatever reason, the parity-mix in the 2022-23 NSFG had a very big change.

One third of the total decline in implied wanted family size is simply a change in the underlying parity distribution: low historic fertility is dragging wanted family size down.

If we look at intentions, here’s what we get:

Intentions are always lower than wants, since that’s literally how the NSFG is structured: women who don’t want another child are never even asked about their intentions, which is kind of weird since of course a women actually could intend another child even if she doesn’t want another child.

What we can see is that from 1988-2010, actual fertility was appreciably above the family size implied by intended parity progression. That’s no surprise, since 30-45% of births are unintended! Then from about 2010-2018 intentions were above actual fertility. Now actual fertility is above unchained intentions, but remains below chained intentions.

Again you can see that there was a huge compositional shift in the NSFG sample in 2022-23 vs. 2017-19.

All three NSFG-derived measures of fertility dispositions point to a major crash in fertility intentions between 2022-23 and probably also wants, though this is partly because of a change in the prior parity distribution dragging intentions down.

If we just ask, “What share of childless women intend another child?” here’s what we get over time:

There has indeed been a huge dropoff between 2017-19 and 2022-23. From 1988-2016, between 78 and 85% of childless women wanted children. In 2022-23, it was 59%.

The main reason I’m not lowkey panicking about this is the NSFG had sample recruitment issues in 2022-23 and added an online mode, and it’s possible what really happened here is they got a bad sample.

After the paywall, I show specific data demonstrating that NSFG method changes CAUSED the decline in desires. Using method-invariant respondents, intentions didn’t fall. Here’s the first graph again, but using only unchanged-methods:

(tons more details after the paywall)

Regardless, let’s look beyond the NSFG at other data sources.

The General Social Survey and Gallup show stability or increase in fertility ideals

Two public survey sources ask Americans about their general fertility ideals. Basically, at the very broadest possible level, how many kids is best or ideal for a family to have? These “general ideals” are among the least predictive of personal behavior (though still, as it happens, highly predictive), but help us get a sense of what the prevailing social norms may be.

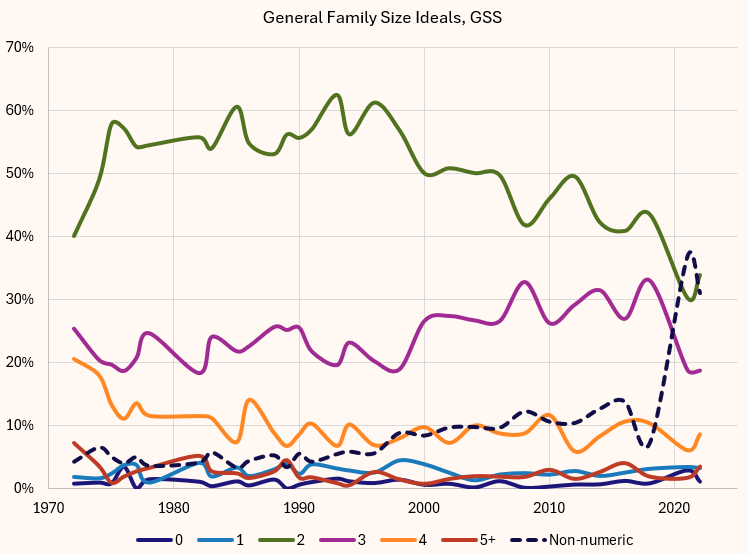

Now, a key note: like the NSFG, the General Social Survey also struggled with respondent recruitment recently, and also switched methods to have a big online component. One massive switch they made is that instead of forcing respondents to independently volunteer non-numeric ideals like “As many as a woman wants” or “As many as God gives them,” in the online mode it was an option respondents could click. That in mind, here’s what the GSS looks like:

You can that between the mid 1990s and the late 2010s, 2-child ideals decline, 3-child ideals rise, non-numeric ideals rise, and other numbers are about stable.

But then in 2021/2022, there’s this massive rise in non-numeric ideals, driven by a decline in 2 and 3 child ideals.

So let’s remake this chart and just look at numeric answers, i.e. assuming that attrition into non-numeric was symmetric (spoiler from conference papers I’ve seen exploring this question, it wasn’t truly symmetric but it wasn’t actually as far from symmetric attrition as you may assume either).

Here, you can see that 3-child ideals declined between 2018 and 2021/22. This decline was offset by rises in 4, 5+, and 2. 0-child ideals also declined.

If we use these ratios to estimate the mean generally ideal family size over time, here’s what we get:

Complete stability.

There was essentially no change in ideal family size in the U.S. between, say, 1975 and 2022.

Just to throw this into sharper relief, here’s NSFG-measured intended family size, NSFG-measured family size implied by parity-progression intentions, and then GSS ideals:

Those are VERY different lines!

Okay, let’s try something else. Do we have a big survey of general ideals which had stable administration method before and after COVID?

Yes! Gallup has asked about fertility ideals since 1936, and they switched to at least a mixed phone/online survey by the 2010s.

Et voila!

Gallup and the General Social Survey strongly confirm each other: American ideal family sizes remain similar or higher than they were in the late-1970s to early 1990s.

So we’re at a conundrum. The NSFG says intended family size is dropping like a rock. But Gallup and GSS say the normative family size is totally unchanged. What on earth is going on?

Theory Before Paywall

I’m gonna give you some cool answers with cool data beyond the paywall.

But before I do, let me give you a theory.

People don’t want kids at all. People want family. They want to raise children, snuggle babies, make a legacy, pass on a culture— they want certain experiences. Those experiences are shaped by social norms.

If the social norm for family life shifts from, say, 2.3 children to 2.7 (what both GSS and Gallup say happened between the 1980s and today), but the cost of children rises from, say, 1 to 2 in “hypothetical cost units,” and if what people desire is not children arbitrarily but a normative family life then…

Rising fertility ideals could cause falling fertility!

Now, empirically, this shouldn’t happen; I’ve shown in prior posts that ideals super strongly predict cross-national differences, etc, etc.

But you can sort of imagine a world where people are like, “Well, I only want kids if I can have 2 or 3, but 2 or 3 isn’t possible, so zero it is!”

I think the fact that almost nobody reports ideals of 0 or 1 for “a family” really tells us this is part of what’s going on because, as I’m gonna show behind the paywall, a lot of people actually report various levels of personal interest in 0 or 1 child, even if they think 0 or 1 child just isn’t right for a family.

So in this theory, the fertility decision process goes like this:

Find a partner who is suitable for starting a family

Determine if you and partner are likely to have enough money/time/resources/support/whatever to hit “close enough to the ideal family experience to make the effort worthwhile”

If yes, create intentions to have babies and have a go at it

But some people nonetheless fail or have to abandon these intentions

This suggests two different thresholded choke points. One, “having a partner” and the other “In expectation, deeming your likely future outcome good enough.”

I know people who really wanted kids, but straightforwardly told their spouse, “It’s zero or three, nothing in between” or “Zero or a boy+girl, nothing else.”

Demographers think of children along a spectrum, where people who desire 2 and end with 1 at least made it halfway there: but what if childbearing isn’t like that? What if people rank-order their preferences in unusual ways?

This is a tricky kind of question to analyze, but I present some suggestive evidence behind the paywall that there are at least a few people who do in fact seem to have this kind of desire, though it’s not extremely common. Many people don’t rank their preferences in a perfectly hump-shaped way where outcomes monotonically worsen with distance from some central estimate, and some people do have bimodal expected happiness distributions.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Lyman Stone to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.