Koreans Have Surprisingly Normal Gender Attitudes

And also Korean housework, Korean careers, Korean fertility, and solving Korean pronatalism, you're welcome, Korea

Korean gender relations are dysfunctional. If you follow The Discourse you know this. Tow examples motivated this post. First, Richard Hanania has a fresh entrance in the anthology of “Korean gender relations are very odd” with a long discussion of conspiracy theories about small penises. I am not going to spend much time discussing that topic, and I agree it is Very Strange. But I am going to talk about this:

So you have this symmetrical paranoia. Feminists in Korea believe they are in danger, despite living in one of the safest countries in the world. Antifeminists believe that they are suffering under an extreme form of misandry, when feminism as a movement is arguably weaker in Korea than it is in any other developed country. From this we may conclude that Koreans are unusually polarized around gender issues, with each sex taking an overly negative view towards the other.

I made a similar claim in response to Darby Saxbe :

This is relevant because of a fantastic recent article on Korean fertility in Works in Progress by Phoebe Arslanagić-Little . I basically agree with her thesis, and think that “unusually politicized and tense gender relations have reduced Korean marriage and coupling to an exceptional degree” is a reasonable theory. But some commenters had other views. One view (which Phoebe obliquely mentions) is that Korea is uniquely sexist. The other view is that Korea is uniquely feminist. It is funny that both of these critiques exist, but the existence of both critiques suggests “unusually polarized” is a plausible hypothesis to explore.

We can do that exploring using data from the Integrated Values Surveys, and that’s what we’re going to do. But under the pretext of writing about gender values and penis sizes, we are ultimately going to discuss Korean fertility rates, because everything in the world across all topics is always actually about fertility rates. Ultimately, past the paywall, we will conclusively solve what’s going on in Korea and answer how to increase Korea’s low fertility. You will see a set of policy proposals which led to a putatively pronatal Korean government official and his delegation walk out of a meeting with me 30 minutes early.

Attitudes About Gender and Politics

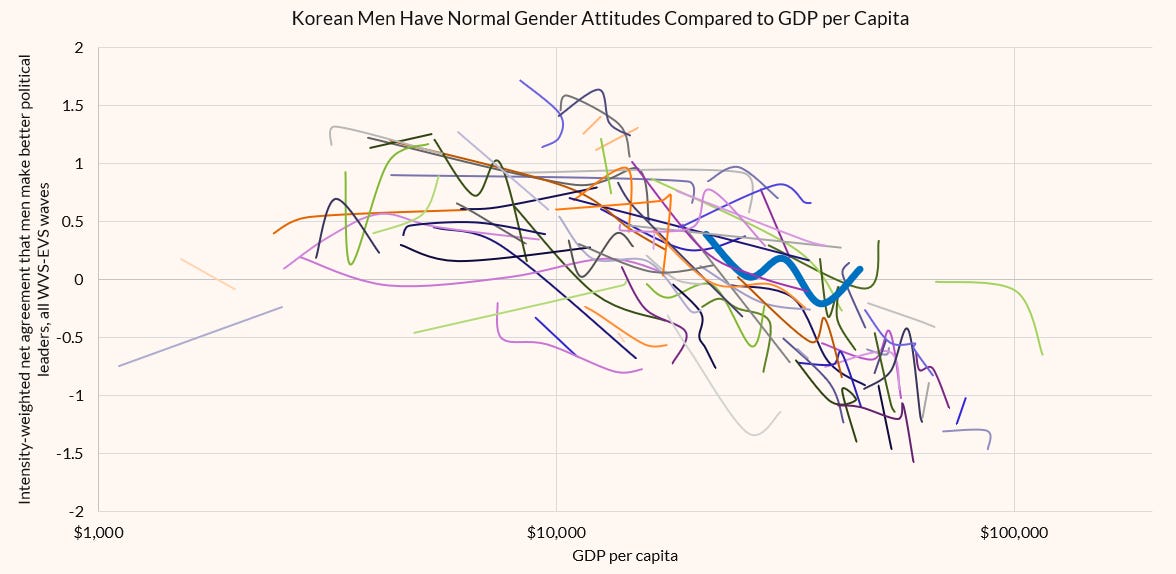

Let’s start with a fairly simple example. Using all available countries and years, here’s how country-average intensity-weighted agreement with the statement “Men make better political leaders than women” for male respondents under 40 has varied across country and time vs. GDP per capita.

The bold blue line is Korea. Higher up the Y axis= stronger belief that men make better political leaders.

You can see that Korea… isn’t that unusual? Korean men seem fairly typical for men under 40 in a country with their GDP per capita. Note that the WVS has been conducted like 6 times in Korea, so we have points for Korea at several different income levels, hence the line across multiple GDP per capita ranges instead of just points.

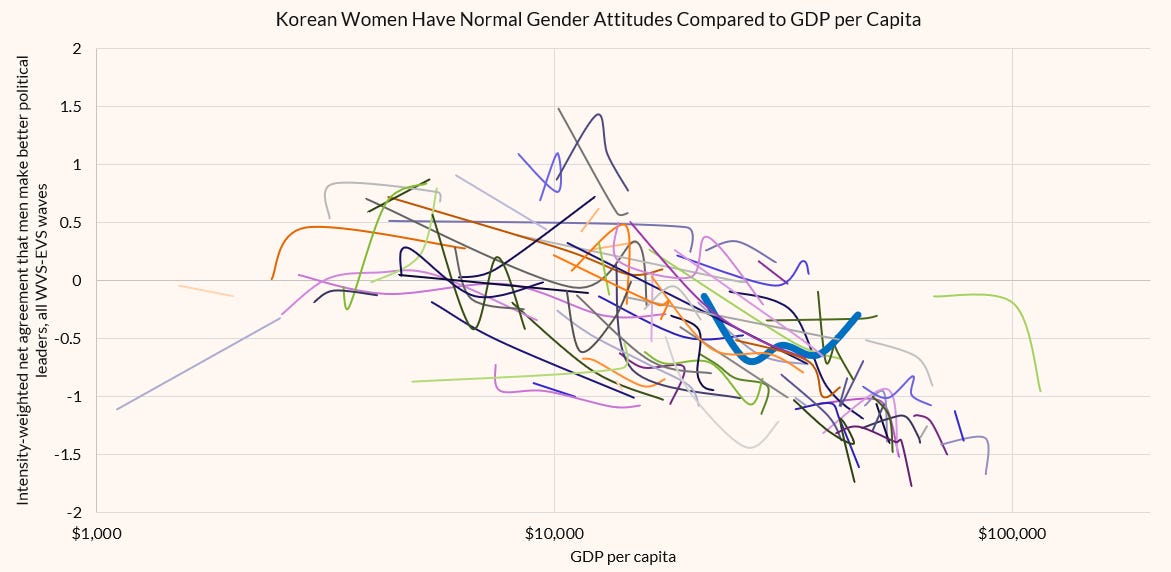

What about Korean women?

Again, nothing to see here. Korean women look rather normal in terms of their values on this question.

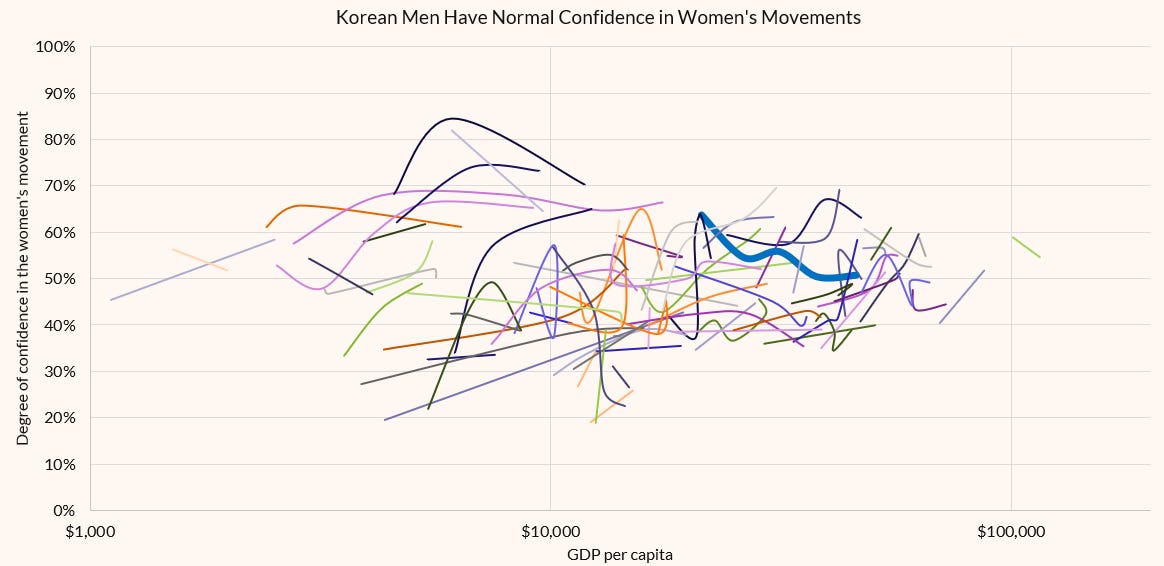

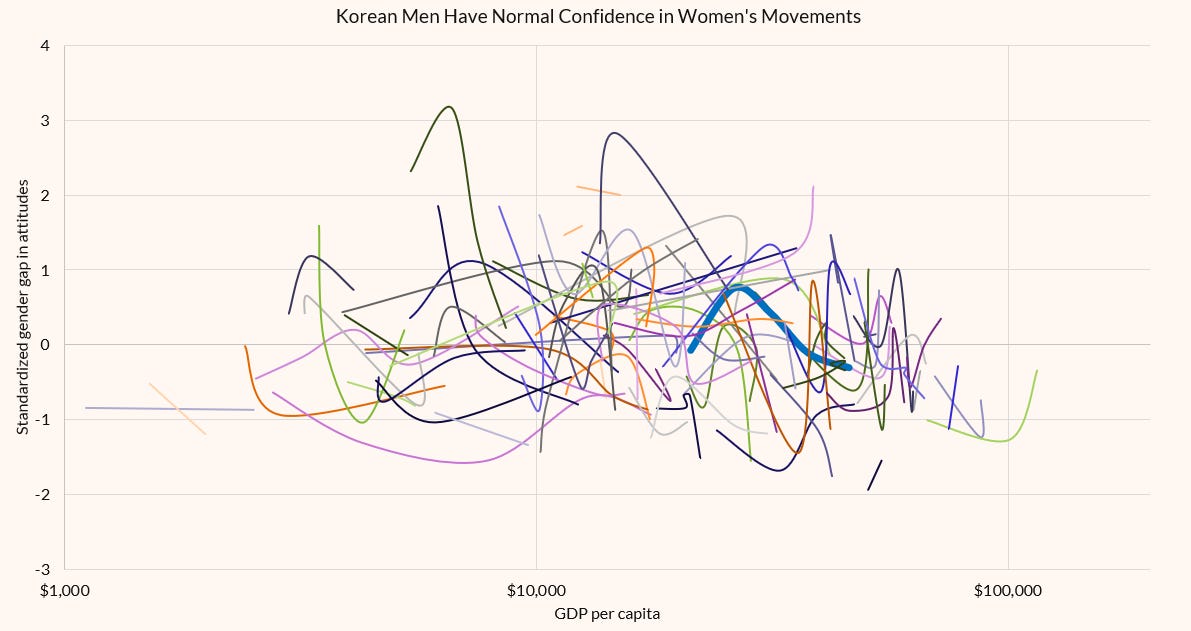

Maybe that’s a weird question. Maybe a different question will tell us more. The WVS also asks if respondents have “confidence in the women’s movement.” Kind of a weird question but it probably captures something like “view of feminist politics.” Here it is for men:

Korean men seem pretty normal. Also I find it interesting that people in poorer countries actually have much more optimism about women’s movements as a source for change! Now, you can see that Korean men have been losing confidence in the women’s movement as the country gets richer. So maybe the direction matters? What do women look like?

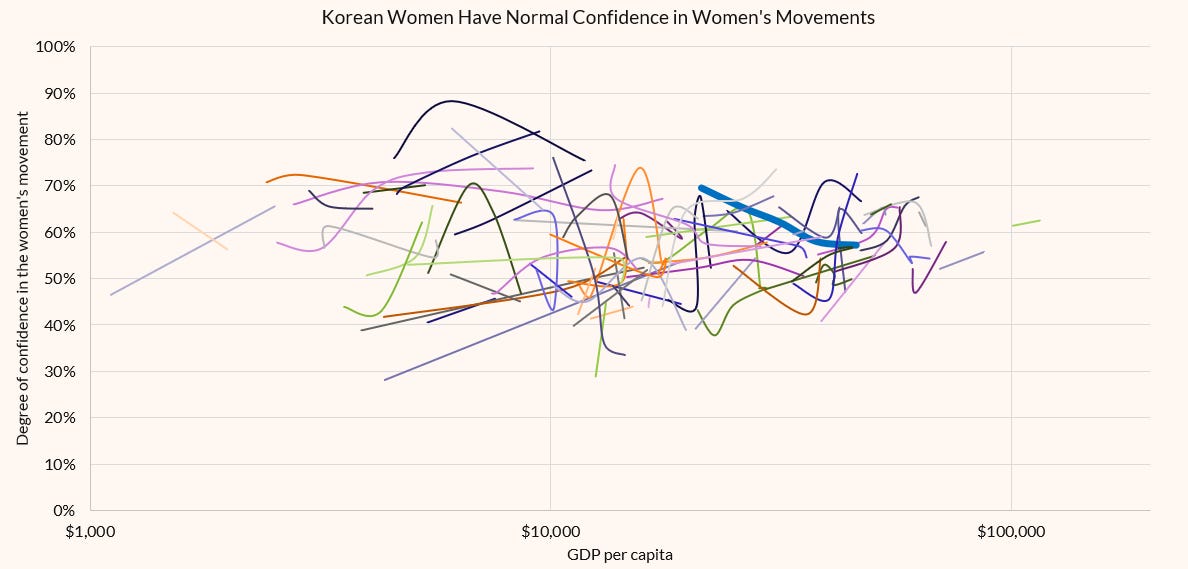

Ah, well, there goes that theory: Korean women also have declining confidence in women’s movements, and also have relatively normal overall levels of this variable.

But maybe there’s a big gap or something? Maybe these gender-specific numbers are sort of obscuring what’s actually an atypically large gap between the genders? So for that I take the country-year-specific gap in responses to the two questions used above, standardize them into a Z score, then take the average of those (inverted for confidence), as a measure of “general gap in views of gender and politics.” Higher scores mean men-are-more-sexist.

You can see that Korea looks… profoundly normal. There is nothing exceptional about the gendered dynamics of gendered political attitudes in Korea.

When I show people this stuff they often just do not believe it. Korea is so obviously unique! How can it possibly be that Koreans are actually normal? There’s no way Korea is normal! If Korea is normal, it might mean the wider world might possibly end up with 0.7 fertility rates and we might face catastrophic global population decline, and that definitely can’t be true, can it?

Housewifery

Maybe you think: okay Lyman, Koreans are not rhetorically sexist about political leadership, but they have super traditional attitudes towards housework: Korean women face a super unreasonable set of home expectations!

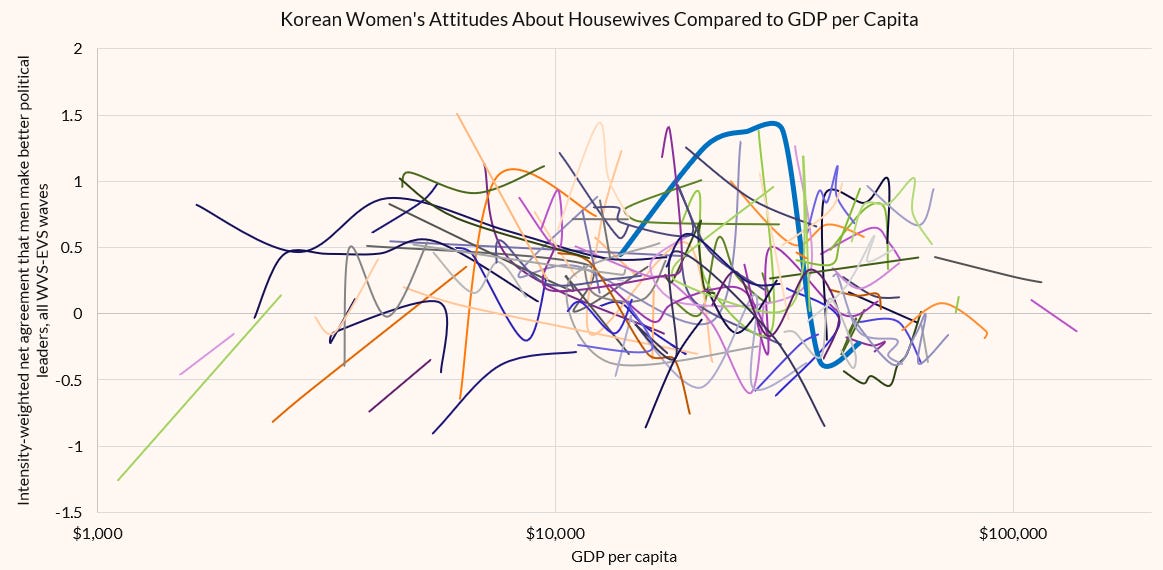

Well, one proxy for that is the WVS statement “Being a housewife is just as fulfilling as having a career.” Here’s intensity-weighted agreement for women:

Here we are finally getting somewhere interesting. You can see that Korea had “normal” housewife-related attitudes, but then Korea got extremely super-pro-housewife for a while, but now in the latest surveys there’s been an absolutely massive swing against housewifery so that now Korea has one of the least pro-housewife attitudes in the dataset.

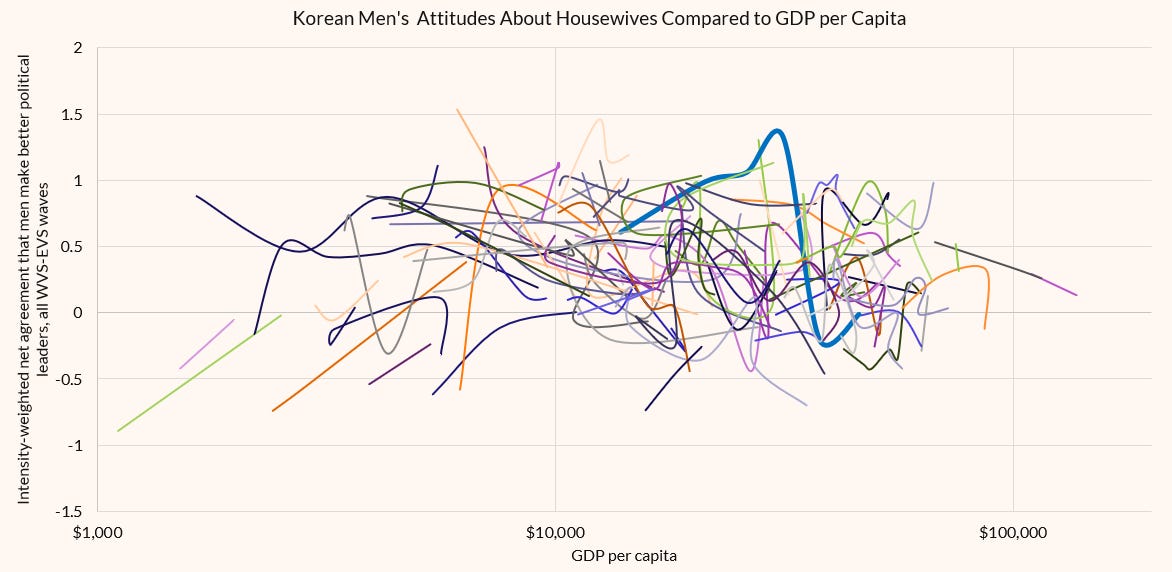

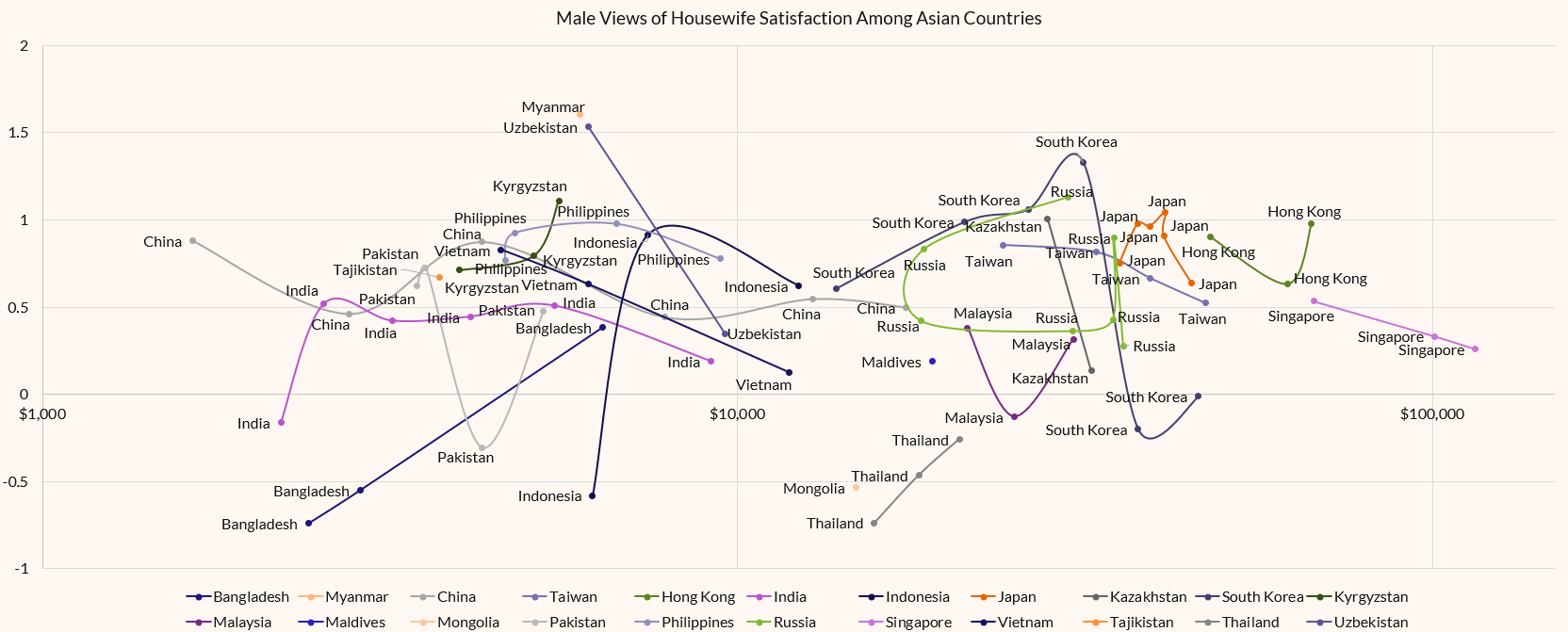

What do men look like?

Very similar!

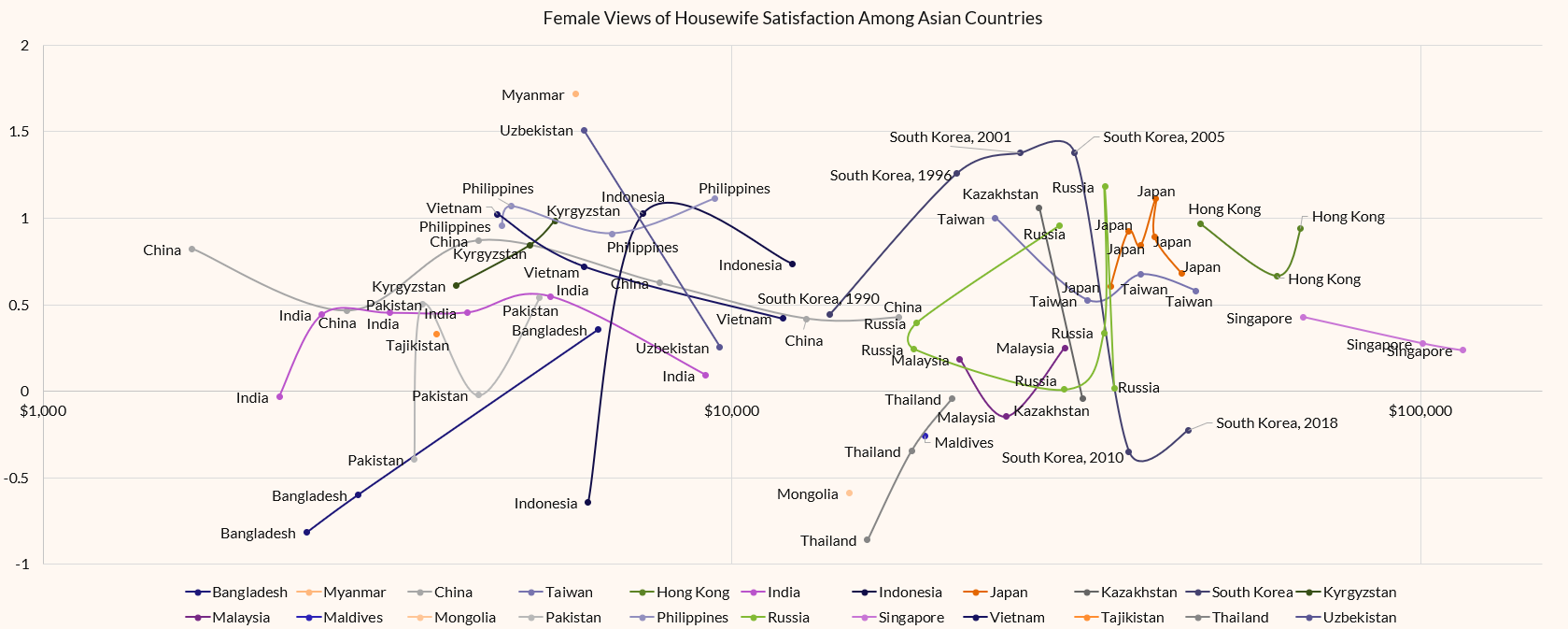

Here’s women again now zoomed in on Asian countries with labels:

You can see, first, that Korean women have unusually negative views of housework for recent Asian surveys. Perhaps only Mongolian women have lower scores in the most recent surveys (Mongolian women were surveyed in 2020, and I would argue any question for Mongolian women which refers to “house” is going to be interpretively challenging).

What’s also interesting is the sheer scale of change in Korea. You can see that China went from being just a couple thousand in GDP per capita to almost $20,000, with basically no change in women’s views of housework. On the other hand, Indonesian women got vastly more favorable to housework, as did Bengali women, as their countries got richer.

If you compare Korea to its nearest cultural peers like Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, or China, you can especially see how unique Korea’s change is: those countries all still have rather positive views of housewifery! Korea does not!

And let’s now look at men in Asia:

Here you can see the same general dynamic again: Korean men were very pro-housewifery, then suddenly very anti-housewifery, to an extent barely ever observed in peer countries.

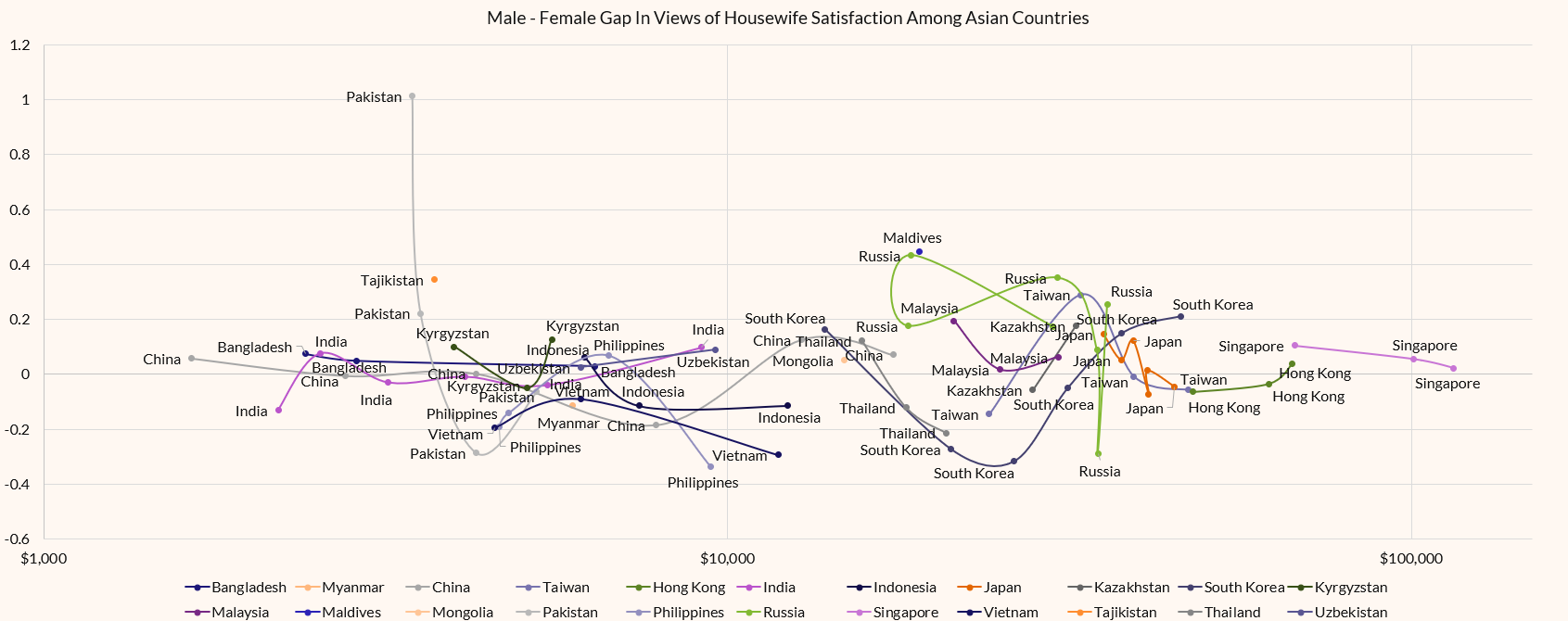

And here’s the gaps:

Now we may be getting somewhere! You’ll notice that for a period, the gap for Korea was very negative- among the most negative observed in Asia! Negative values mean female respondents under 40 valued housewifery more highly than male respondents under 40. Or, rather, that young women saw greater relative satisfaction for themselves in being a housewife than young men thought young women saw. Basically, young men relatively over-rated how much young women preferred careers. Those two very negative values occurred in 1996 and 2001.

But in the latest surveys, the gap has flipped. In the 2018 survey, Korean men now estimate much higher satisfaction for housewives than young women expect. The only other countries with similar gaps in recent surveys are Tajikistan, Maldives, and Russia.

But still… the gap for Korea isn’t actually that extreme. Were I to expand to the entire globe you’d see many countries near Korea’s current levels.

So here’s where we stand:

At the level of social values, Korean men and women seem mostly rather normal. There is nothing exceptional in their views of women as housewives, women’s political agency, or female leadership. If gender polarization is giving rise to penis-size conspiracies, that’s weird, because lots of countries have had more severe gender-differences in attitudes.

You could tell a story where “rapid social changes give rise to paranoid conspiracies, sometimes about penises.” To the extent there’s anything interesting going on it’s a massive nosedive in views of being a housewife between 2000 and 2020, such that now Korean men and women alike see being a housewife as extremely, unusually unsatisfying for women.

So now we want to ask: has Korean culture changed much in other ways that would allow us to see what happened in the last two decades?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Lyman Stone to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.