This post is speculative. But I’m writing it now, before the trends I fear come to pass, to lay down a marker. As a note, longtime readers know that I am biased on this issue. I’m a conservative, traditionalist Christian who believes that premature termination of human life solely for the purpose of alleviating suffering is immoral, since the experience of suffering is part of our union with Christ, and the occurrence of suffering is a primary occasion for the virtuous vocations of others. However, I will not lean on those arguments here, though careful readers will notice that my underlying implied view here is that moral virtue is not only virtuous but also imbued into nature in such a way that virtuous norms tend to generate desirable social outcomes, whereas vicious norms tend to generate undesirable social outcomes. Nonetheless, you needn’t accept my moral presuppositions to accept the reasoning below; I note it merely so that you can understand my biases.

A second bias here is that a large share of my income comes from providing research to pharmaceutical companies who are deeply invested in treating, curing, or managing diseases. Widespread choice of palliative care and euthanasia over treatment directly threatens my ability to feed my family, so I have strong economic reasons to prefer that people would continue to choose treat-and-suffer rather than ease-and-die. But again, you needn’t share my economic interests to accept the reasoning below. I simply note it so that you understand that I am not strictly neutral.

I want to make two arguments. First, a counterfactual history; second, a speculative future.

My basic argument will be this:

If euthanasia becomes widespread for specific often-but-not-always lethal conditions, treatment quality and options for those conditions will cease to improve and may rapidly decline.

As a result, younger and more survivable sufferers with those conditions will face worsened prognosis caused by the expansion of euthanasia, and will likely be nudged into euthanasia they might not counterfactually have desired.

1. What If Euthanasia Had Always Been Popular?

Indulge me in a historical counterfactual. Imagine that it’s 1525 and the Reformation is winding up. Imagine that by some quirk, the Reformers all came to reject the Catholic opposition to abortion, infanticide, and euthanasia. Imagine instead that the Reformers all came to endorse something more like the beliefs of then-rising-in-popularity Edo-period funerary Buddhism, and as a result, Protestant rates of abortion and infanticide rose to 30-50% of conceptions. Virtually all unhealthy children are killed in infancy. At the same time, Protestant doctors invest efforts in treating disabling and nonfatal conditions, but no effort at exploring treatment for foreseeably life-ending conditions. Over the years, Protestants get good at end-of-life pain management, but ultimately popularize euthanasia. By the 1840s widespread access to opium means that pain-free euthanasia is widespread: virtually 100% of forseeable deaths are from euthanasia, perhaps 30% of deaths overall. Over the 19th century as medicine for early deaths improve, more deaths come from causes with drawn-out suffering. By the mid-20th century, 50% of deaths are from euthanasia.

In this scenario, do you think there is as much research effort poured into treating late-in-life causes of death which, when treated, only extend life by a year or two, and QALYs by even less?

To me, the answer is obviously “no.” The herculean efforts the West put into treating these diseases arose from the specific cultural context which made it culturally taboo to just quietly knock off suffering old people. You can’t kill them, you have to treat them. Classic “Hippocratic oath” kind of vibes.

I think that if the West had adopted the value set I describe during its historical scientific development, life expectancy at conception would be ~40% lower today, life expectancy at birth ~25% lower today, life expectancy at age 1 ~10% lower, and life expectancy at age 70 ~10-25% lower.

Your exact percentages may vary, but I cannot fathom arguing for 0% lower. And I think the best evidence of this comes from Japan. When Japan began to industrialize after the Meiji restoration, the modernizing government became deeply, seriously convinced that widespread infanticide and the social acceptability of suicide were major obstacles to modern development. As such, they created a special new police force to surveil pregnancy and prevent infanticide: Japan still has one of the most complete systems of pregnancy registration in the world today, and occasionally publishes data from it. In 1873, they also abolished judicial seppuku, and launched a campaign to suppress voluntary suicide.

In the paradigmatic test case of Japan, modernization involved a massive overt change in public norms against infanticide and suicide.

To me, that suggests that it really is the case that societies of rapidly improving life expectancy and health are not societies of suicide and infanticide. The cultural norms that induce smart people to invest in finding ways to help old people live incrementally longer or be incrementally more comfortable are not the cultural norms which induce the public to accept widespread suicide as a solution to possibly-terminal suffering.

2. What If Euthanasia Became Genuinely Popular?

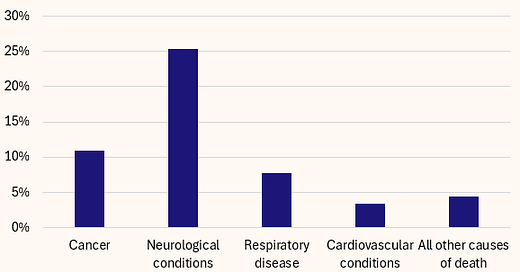

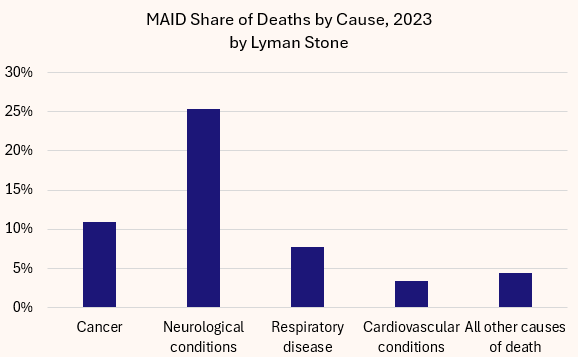

Now let’s imagine what would happen if euthanasia really became widely popular. The leader in this case is Canada, where maybe 6-7% of deaths involved euthanasia (“Medical Assistance In Dying” or “MAID”). That doesn’t seem super high.

But here it is by major cause group:

On hand I didn’t see more detailed cause breakouts, so this is what we’ve got. But the key point is this: solidly a quarter of neurologically-related deaths in Canada are already actually people who died when a nurse or doctor injected them with lethal chemicals at their request, and over 1-in-10 cancer deaths.

Imagine you have a rare and dangerous cancer. You are 56. The typical person with this cancer is 67, and their prognosis is bad, maybe 75% mortality within a year. But for you, at your age, it’s more like 40% mortality within a year. But 80% of people with this condition have less than a year to live.

Now imagine two different scenarios. In scenario 1, 75% of the people with <1 year to live pursue palliative care and then euthanasia instead of uncomfortable treatment with low success odds. In scenario 2, 10% choose that option.

Here’s my math:

The key takeaway is “What share of people who get this condition pursue the uncomfortable-but-possibly-lifesaving treatment for it?”

In the high-euthanasia share, just 38% do. In the low-euthanasia share, 91% do.

Now that’s in partial equilibrium.

Now imagine general equilibrium:

How many specialists in this treatment exist when 91% of diagnosed cases pursue treatment? And how many when just 38% of cases pursue treatment?

The obvious answer is that when few people pursue treatment for a disease, fewer doctors specialize in it, fewer researchers innovate in it, etc, etc. Diseases attract specialists and innovation for many idiosyncratic reasons, but the central issue is always going to be “There are lots of patients who want to get a treatment.”

For diseases where a “treatment” only usually means a few more months or years of life after an already long life, and where a “treatment” is almost always a choice to have some amount of short-term additional suffering, the availability and normativity of euthanasia will reduce demand for treatment and thus reduce treatment options.

This may seem like a very niche kind of disease, but it actually describes tons of diseases, most especially cancers, but also many neurological conditions.

These are conditions where we should want patients smashing down the doors demanding medical innovation, because these conditions are the current “hard limits” on human longevity. Widespread euthanasia will erode that demand.

The upshot is when an unusually young or good-prognosis person gets the disease, they will have a much harder time finding specialists, and have fewer innovative treatment options.

Seriously, ask somebody who has a really rare disease how easy it is to get treatment and specialist care. It’s incredibly hard. You end up flying around the country for doctor’s appointments. It sucks. Making specialist care more widely available for a given condition boosts survival from that condition.

Thus, widespread condition-specific euthanasia may actually worsen the prognosis for that condition.

The choice to suffer is a choice to fight, and the choice to fight is a choice to drive market demand for treatment, and the choice to drive market demand for treatment is the choice to save future human lives.

Point blank, my argument is that euthanasia threatens to undermine the incentive structure driving a lot of medical advancement and innovation, and as such undermine actual health, and perhaps then drive even more euthanasia. It’s not hard to imagine some rarer conditions reaching nearly-100% euthanasia rates.

And so, coercion

Coercion is a tricky word and people debate what it means. But here I mean just “you won’t have options.”

If you get a condition where everybody else with it chooses euthanasia, you eventually won’t have a lot of other care options.

Doctors won’t have experience treating you. Drug companies won’t produce the medicines that might save you. If clinical trials happen at all, they won’t proceed to commercial stages.

I have a dear friend whose child has a severe genetic condition; they entered a trial for a somatic gene-editing drug. The drug worked, cured the condition. The kid’s life expectancy rose from <10 years to >60 years from one drug with no continuing need for medication. The trial worked perfectly. The drug, however, will never reach the marketplace because the condition is too rare, the drug too costly and experimental, and so it won’t be viable to market the drug.

Beyond lack of options, if 90% of patients choose euthanasia, medical staff and insurers will almost certainly nudge, cajole, badger, and pressure patients to take that route. Treatment will be treated as nonstandard, requiring justification, etc, etc.

None of this will be conspiratorial. There won’t be death panels killing off olds. Your doctor isn’t gonna wait until you’re not looking and jab you with murder juice. It will all be perfectly normal, hygienic, medical. Consent forms will be signed. Due diligence will be conducted having verified that there were no reasonable treatment options. But the reason there were no reasonable treatment options will be that before you ever got sick, other people choose euthanasia over suffering, and as a result, you will preventably die earlier and without even an option of fighting.

Very thoughtful piece, thank you. Came over here from Twitter where we have some mutuals. I think your overall case about market demand for treatment is solid, but a couple of points…

First, I think you’re drawing an unfairly strict dichotomy between treatment and MAID. This breaks down on two different fronts: some people will decline both treatment and euthanasia, which has the same effect of reducing market demand for treatment. And some people will GET both treatment and euthanasia, which provides market demand. So it seems to me that you are likely overstating the impact of the availability of euthanasia on demand.

Second, most people don’t jump straight to euthanasia; they try what they can for as long as they can bear to, and only turn to euthanasia when treatment has failed, or their suffering grows too great, or some combination thereof.

Third, what is the obligation of the suffering individual to contribute to market demand for treatment? I think you’re inventing a social obligation that most people would not agree exists.

Why should someone who has, say, a cancerous tumor have a greater obligation to provide market demand for treatment than anyone else? Do I have an obligation to expose myself to radiation in order to give myself a similar tumor in order to create market demand for treatment? Clearly not.

If there is such an obligation, surely it would apply to obtaining treatment, and not just avoiding euthanasia—so if you don’t want to allow euthanasia, would you also make treatment mandatory in order to maximize demand?

Finally, I think it’s worth pointing out that individual suffering is not the only mechanism for creating demand. We could offer grants and prizes (and indeed, do)—a billion dollars for curing a rare disease, say. This is probably a better path forward than expecting market demand to incentivize the development of treatment for very rare diseases (very cool story about your friend’s kid who benefited from gene editing, BTW).

in short. it turns out that killing people is cheaper than taking care of them. to me it was obvious that with an aging population this is really what is behind the euthanasia expansion