Thou Shalt Not Lie

You Must Admit to Being Pronatalist

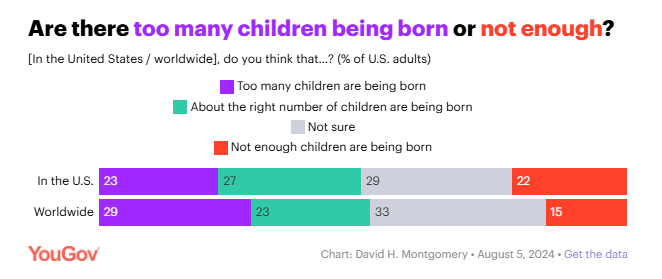

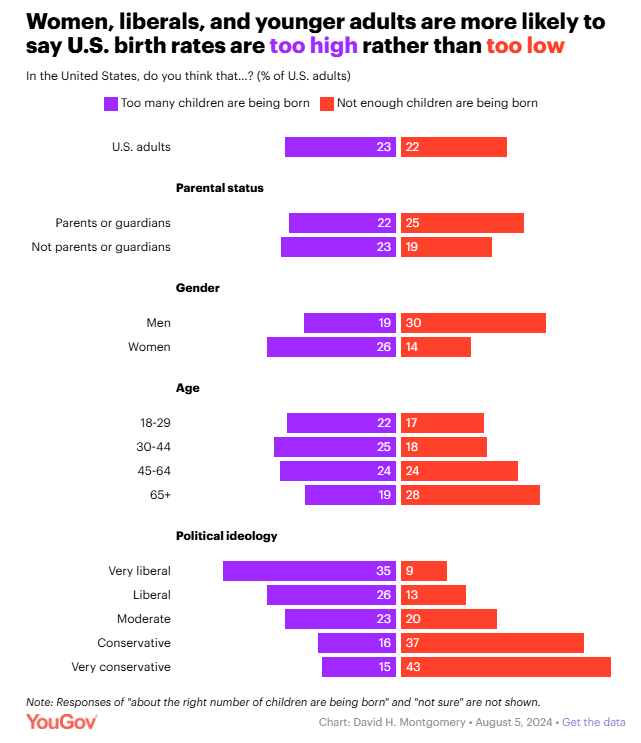

Many people are worried about falling fertility. I think probably not enough people. Here’s what YouGov says:

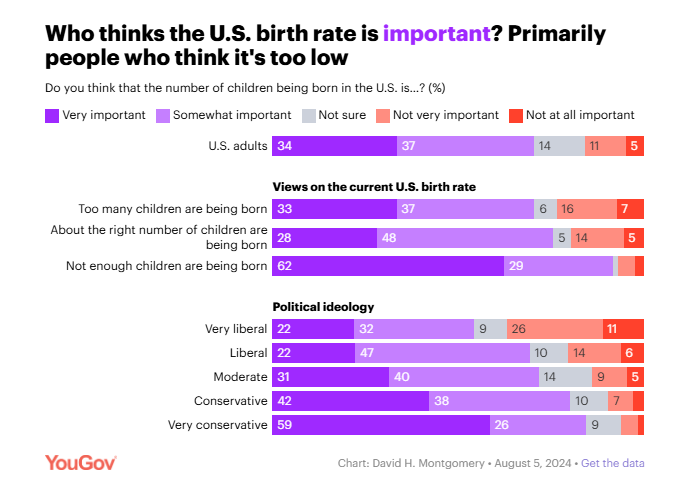

Notably, people who think falling fertility is a bad thing also just care a ton more about the issue than other people:

As a result, people worried about falling fertility tend to be sort of intense. They look you dead in the eyes and say things like “Falling fertility is an existential issue, it’s the end of civilization, if we don’t solve this nothing else matters.” And that kind of intensity tends to feel a bit cringe since we live in a depraved world where things like “Sincerely believing history isn’t over and things really matter” are cringe.

Because this kind of fertility-concern is a bit cringe, there’s a real push by people who are worried about fertility but not so cringe-ily intense to find a way to rebrand to separate the cringe concern from non-cringe varieties.

This has been ongoing for a long time, but we have an incredibly clear-cut case recently in Ivana Greco’s recent essay, “Why I am not a pro-natalist.”

Her basic argument is, helpfully, right in the opening paragraph:

It is topical these days to talk about pro-natalism, or the idea that we should socially engineer higher human birthrates. The pro-natalist movement has various iterations, some of which are perfectly reasonable, and others of which are deeply concerning. Regardless, I can’t call myself a pro-natalist. I’m certainly not a libertarian, but social engineering often makes me nervous, and particularly so when it attempts to impact one of the most personal and serious decisions a person can make: whether to have a child. Instead, I think of myself as an anti-anti-natalist, or opposed to the philosophy that we should have fewer children. I hope that governments can find a way to support families in having the children they want to have; rather than trying to convince them to have more.

So she’s not a pro-natalist because she opposes “social engineering,” but she does want the government to enact policies to help families have the children they want to have.

So we are going to look at three key points in her essay:

Is there any difference between the cringe pro-natalism she dislikes and the based pro-family policy she likes?

Do pro-natal policies work?

Does it matter what we call it?

My argument will be: 1) Ivana Greco is engaging in a form of rhetoric which most people will see as dishonest once they appreciate the math behind it which she studiously declines to mention, 2) pronatal policies will and do work, 3) but if people who care about this issue won’t stand up and say “more babies is good” explicitly then the battle is lost and family life as we know it really will cease. You must call good things good.

This article will not be paywalled because last time I argued with someone behind a paywall you poors whined about it. SMH.

What Is Pronatalism

Where It Comes From

Pronatalism is a Latin-root word meaning “in favor of births.” If you prefer a Greek-origin version, you might say “protokism.” If Anglo-Saxon roots are your jam, then you’d call this ideology “forbirthism.” These are linguistically identical words. If you are “for births,” then you are also “pro tokos,” and you are also “pro natal.” Same-same-same.

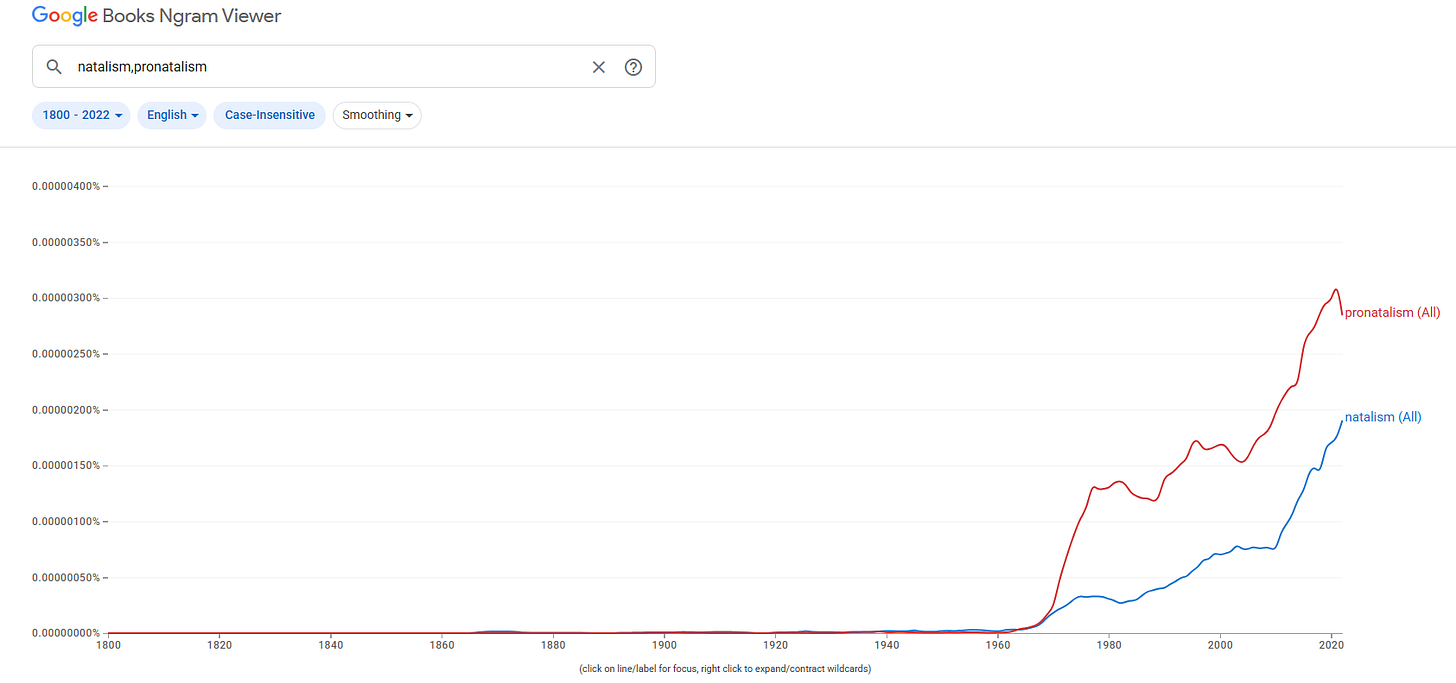

Pronatalism entered the English language very recently:

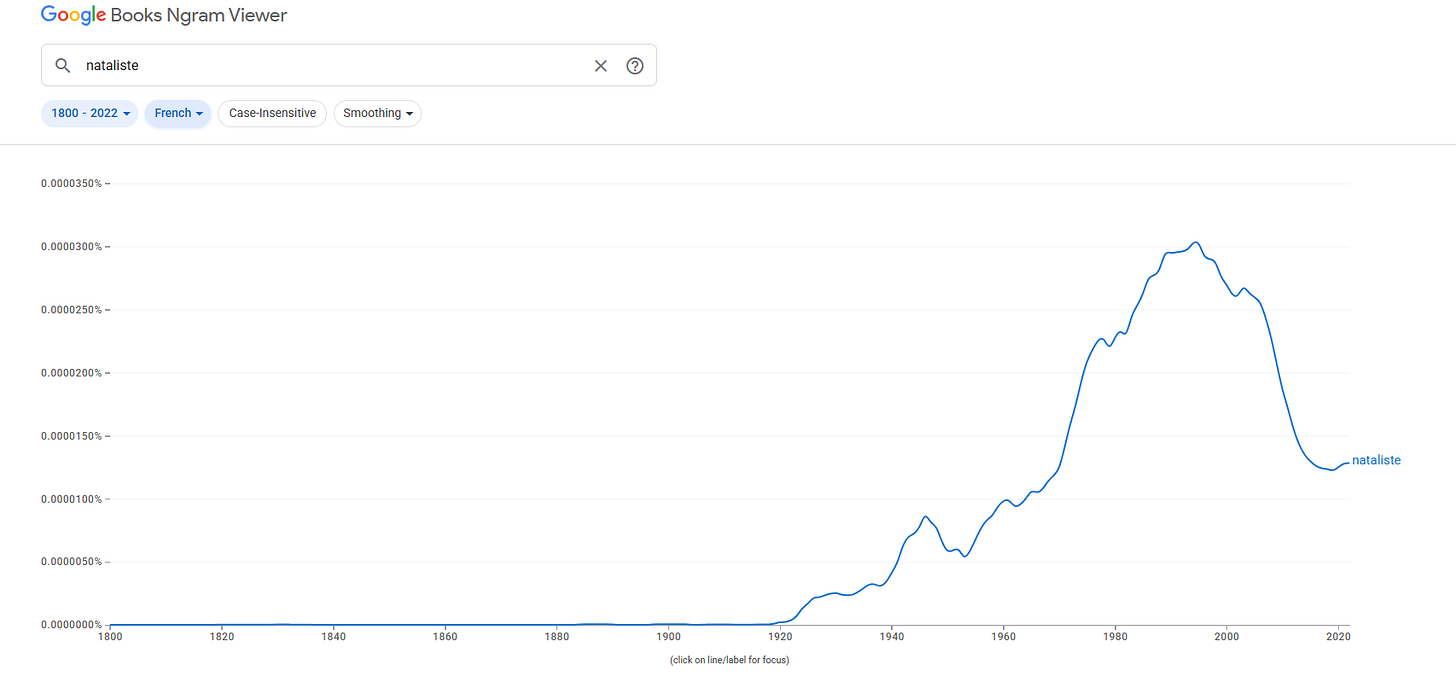

The word entered English from French. French got the word in the 1920s:

The reason France got the word “nataliste” in the 1920s is because of how embarrassing it was to be saved by the Brits and the Americans, and they realized their unusually low fertility was going to lead to German conquest in the future, so they invented an ideology to boost births.

But English-language birth rate concern predates pronatalism per se. Trent McNamara’s Birth Control and American Modernity is a very nice book on this, outlining some of the late-19th/early-20th century concerns about “race suicide” that are similar to some strands of pronatalism today.

Indeed, pronatal policy concerns are ancient. Richard Togman’s Nationalizing Sex is a fun read on that topic. You can find pronatal policymaking in ancient China, ancient Rome, and many other places; but most intensely in medieval and early modern France, because French people have been forgetting to have babies for a long time. Because fertility is always a huge fitness loss for individuals (i.e. it costs energy to have and raise children), but simply is fitness qua fitness for genes and communities, but because Fisherian reasons mostly preclude recent historic selection on genes in really potent ways, human history is basically mathematically guaranteed to be replete with collective pronatal ideology in conflict with individual incentives to socially freeride through childlessness. This is an intrinsic evolutionary struggle in human societies which cannot be avoided, which is way almost all long-lived societies have religions which institute norms that induce people to have children rather than just have lots of handjobs and blowjobs, etc.

Thus, when we think about pronatalism today, we should not think of it as a a debate that started in 1960 or 1920 or 1890— we should see it as a mere continuation of the argument humans have been having since at least the dawn of agriculture, namely, “Having children is hard and costly for individuals, but very good for societies and cultures: how can societies and cultures induce individuals to sacrifice themselves for the group?” If you aren’t having that debate, you aren’t even doing the table stakes for the conversation, you literally are the reason fertility is low. But it’s key to realize this debate is not about post-Enlightenment “individualism”! My thesis is that this debate has been ongoing basically since forever ago. It has always been true that having and raising children was costly and hard and many people tried to avoid having to do it. It has always been true that some people found ways to succeed at avoiding this task. It has always been true that fertility staying about prevailing-mortality-conditions-determined-replacement was largely an outcome determined by effortful cultural action to create norms that generated children. I’m not gonna belabor this too much because, hey, that’s my long-term book project I’m working on! But suffice to say, if you aren’t thinking about the fitness tradeoff, or if you think the fitness tradeoff was invented in 1750, you just don't have the vocabulary to participate in this debate, and you should let the adults talk in peace.

Rival Definitions

There are different definitions of pronatalism. I have written a nice article about these definitions. I will quote from it at length. As a reminder, I am the Director of the Pronatalism Initiative at IFS. So if anybody has maybe done some chewing on “what is pronatalism,” it’s this guy right here.

A lot of different viewpoints fall under this extremely broad, simple definition. But these views can be grouped into three different and general categories.

Freedom-focused Pronatalists. The first is what scholar Trent Mcnamara has called “liberal pronatalism,” or what we call “freedom-focused pronatalism.” Freedom-focused pronatalists (like our Pronatalism Initiative) want more children because it’s important to human flourishing for fertility to be close to desired levels. Big deviations (higher or lower!) from desired fertility represent basic failures of human freedom, agency, and autonomy. Because the defining principle here is human freedom, our approach also constrains the policy options available to us: by necessity, we oppose policies that manipulate birth rates in ways that constrain human freedoms or diminish human dignity.

Economic/Structural Pronatalists. Other people may want more babies for technocratic reasons: higher GDP, more innovation, more conscripts for an army, balancing Social Security. This group can broadly be called economic or structural pronatalists. Truth be told, most people in this category don’t call themselves pronatalists. They’re worried about population structure changes, maybe think fertility should be part of the solution, but wouldn’t identify with the term “pronatal.” This group has a lot of flavors within it: some might be willing to constrain human freedom to improve demographic fundamentals, others might not.

Communitarian Pronatalists. The final group of pronatalists can be called communitarian pronatalists… Communitarian pronatalists want more babies because it’s important that some group be perpetuated. In the majority of cases, communitarian pronatalism is wholesome and decent: parents who have a baby to give their parents a grandchild, or to carry on the family legacy, are espousing a version of communitarian pronatalism. So are religious people who see in their children a promise of the future for their community. Likewise, Ultra-Orthodox Jews encouraging high fertility partly to repopulate after the Holocaust are a clear example of communitarian pronatalism, and while not everybody might want to have Hasidic family norms, these varieties of pronatalism range from inspiring at best to at the very worse, inoffensive.

There is, however, a seedier side to communitarian pronatalism, when the “community” in question is an imagined community such as a racial or national group rather than an actual human-scale community like a family or congregation. The vast majority of communitarian pronatalists have some actual real-world community they want to see perpetuated, but some use the language of communitarianism to concoct the notion of racial communities. Most famously, the Nazis promoted extremely aggressive pronatal policies for the races they saw as desirable, while exterminating those seen as undesirable. In China today, the communist government actively promotes higher fertility for the Han Chinese majority, even as it forcibly sterilizes religious and ethnic minorities and kidnaps their children. Thus, communitarian pronatalism covers an enormous range of political territory, from simple love of family to the bonds of faith and creed, to—in some of the worst cases—racial supremacism and genocide. It is this last strand of communitarian pronatalism that has given pronatalism, writ large, a bad name to many demographers.

At the Pronatalism Initiative, our main perspective is that of freedom-focused pronatalism. We think the main problem of low birth rates is that people are not enjoying “freedom to have family” to the full, and the solution is to unshackle them from whatever unreasonable obstacles may be holding them back. Of course, we recognize that economic pronatalism is important as well, and that, for most individuals, communitarian pronatalism is personally motivating (the family is, at its core, the most basic and central “community” in society). But when it comes to defining our policy vision and engagement with the public, our focus is on the freedom to have a family, not the beneficent effects of fertility on the economy or any given community.

So let’s be clear. The flagship Pronatalism Think Tank, the only American think tank (until literally last week!!) that actually has an explicit policy mandate to boost births, the organization producing basically 90% of the graphs you will see self-identified pronatalists sharing, has given an explicit definition of pronatalism, and it’s “helping people have the kids they want to have.” Practically speaking, pronatalism=“helping people have the kids they want to have.” That’s what it means in practice in America in this the 2026th year of the reign of our Lord.

But how can that be? How can it be that “more births” literally just means “helping people have the family they want to have”?

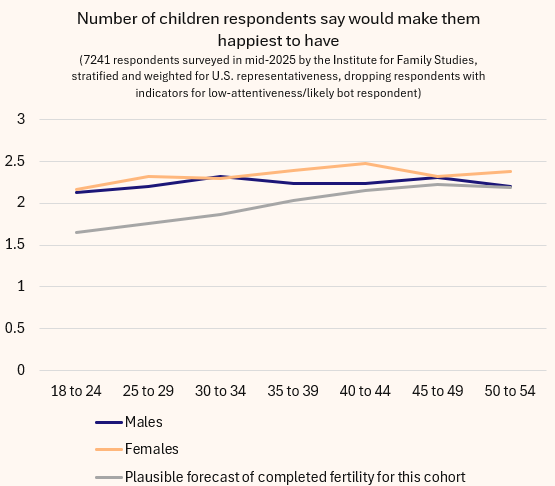

Well… quick reality check, here’s the number of children women and men said they wanted in a 2025 survey I conducted, vs. a credible projection of the completed fertility we can expect for these cohorts.

It’s not a mystery what people want to have: they want more. Current 18-24 year-olds are likely to end up with 1.6-1.7 kids, but desire about 2.1-2.2. If everybody had the kids they want, fertility rates would be ~25% higher!

Thus, when Ivana Greco says “I don’t want to social engineer higher birth rates I want people to have what they want to have, and that’s different from pronatalism,” she’s doing a bait and switch that people will tend to view as dishonest. The reason I think people will view it as dishonest is because I have surveyed this strategy and focus-grouped it, and “Yeah pronatalism is bad, we’re just profamily, but since fertility is below what people want, we are going to do pronatal stuff” causes people to rate the speaker as dishonest and manipulative. Unfortunately for proprietary reasons I cannot show you the graphs, sad. But it just is the case that telling people “I’m not like the gross pronatalists who want to socially engineer you… but by the way I’m gonna do all the birth-promotion policies…” is a bait-and-switch that registered voter samples see straight through and dislike. Honesty is always the best policy. If you think it’s a bad thing that birth rates are where they are now, just say it, “I’m a pronatalist.”

The simple truth, and I am begging the family-policy-concerned citizens of Substack to comprehend this, is that if you are, say, a political candidate, and you wanted to know “What messaging on birth-rate-related policies lands best with voters?” the answer is “Shut up— implement policies without any explanation at all because everything you say on this issue is toxic” and the second-best answer is “Take it head on and say it’s a tragedy that birth rates are low and you want them to be higher so you’re doing stuff to help people have more babies if they want to.” Genuinely the worst answer is, “Tell people it’s not really about birth rates it’s about something else when you’re doing stuff that’s obviously about birth rates.” Okay that’s not true the actual worst answer is, “Be racist about it.” But besides that, trying to lie about the fact that you’re trying to raise birth rates wins you zero votes and loses you many.

So let’s be clear:

when Ivana Greco locates pronatalism in a recent debate about population decline, she’s not correct. Pronatalism is part of a thousands-of-years-old debate about individuals, fertility, and society, which rears its head recurrently throughout history. our latest episode is just that: the latest episode. people concerned about family should play the long game.

actual existing political pronatalism is… exactly the ideology Ivana Greco espouses: helping people have the families they want. she’s just making up a rebrand

and it’s a bad rebrand! people really hate dishonesty! “genuineness” in a politician is something Americans like!

And finally:

Ultimately, although pro-family policies may look similar to pro-natal policies, the goal is very different: it involves government coming alongside families to help them achieve the goals they have set for themselves. Rather than top-down social engineering, it is driven by parents themselves: a strategy I think much more appropriate for a country that prides itself of being a democracy that responds to the will of the people!

we’re literally talking about the same policies here my goodness people this is crazy, just admit you’re a pronatalist!! you are! stop lying! “i’m not an arrogant mean too-online guy, i’m a Bold Truthtelling Public Intellectual” c’mon folks we know that’s a lie, i’m an arrogant mean too-online guy. own who you are. want more babies? pronatalist!!

Does Pronatalism Work?

Ivana Greco says:

In addition, it’s also not clear that most pro-natalist proposals have much in the way of evidence behind them. Countries that have put significant effort into boosting fertility rates have not had overwhelming success. In Hungary, for example, despite years of government support for marriage and families, the fertility rate is 1.3 children per woman. Ultimately, it is probably the case that it was much easier to decrease fertility than it will be to raise it again. This follows, of course, from a more general principle that it’s easier to break something than to fix it.

sound of Lyman breathing into a bag

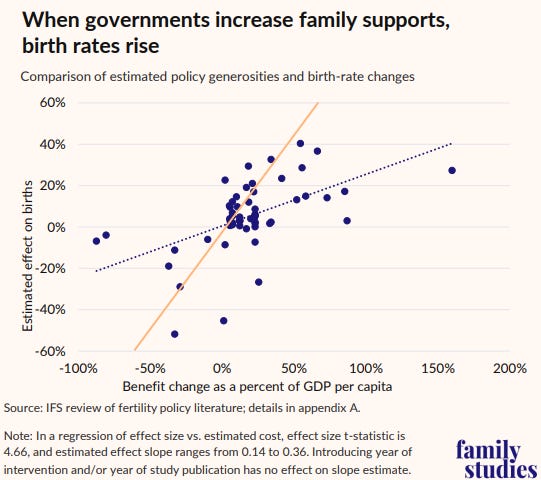

Since then 5 more have been published and they do not alter the slope of the line. If we drop the outliers, the slope gets steeper, i.e. more effective. I haven’t finished doing the Cohen’s-d calculations and effect size stuff for formal meta-analysis, but my incomplete work on it looks like not too much evidence of publication bias.

The evidence is very clear, people! Pronatal policy works! When you incentivize people to have kids, they have more kids!

In general, a benefit with a present discounted value of 1% of GDP per capita increases fertility by 0.14-0.36% (call it 0.25% for simplicity). So if you implemented a $10,000 baby bonus in the U.S. (11% of GDP per capita), you’d expect fertility to increase about 2.6%. Extrapolating, it would cost about 10% of total GDP to get fertility to replacement rate in America only via fiscal supports of this kind. This is about what we spend on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid combined, so yeah it’s a ton of money, but it’s not out of scale of stuff we already spend on old people or poor people. Somebody else built this simulator totally separately from me, and his math yields approximately the same result.

Folks, incentives matter. When you change the incentives for behaviors, behaviors change! If you don’t believe this is true, cool, try to implement communism and see what happens.

The problem, of course, is that while incentives matter, kids are an incredibly costly choice. It has always been thus; as I have written above, so I say it again: there has always been intrinsic conflict between individuals bearing the costs of fertility and societies needing fertility thus seeking mechanisms to induce individuals to bear children. Those mechanisms include financial/material transfers, alloparental support, regulation of sexual and reproductive behavior, moral suasion, interventionist grandparents, religious ideas, and many others. Life… finds a way.

But, and this is the super important part, not every way that life could find is created equal! I do not want the future to be Amish because I do not think the Amish way of life is the highest and best use of our God-given capabilities. For those of us who think modernity has at least several good parts to it, finding a way to do pronatalism without destroying the good parts of the system is the task before us.

Right now, there isn’t enough research on how to do this. Too few young researchers take up this topic as their primary field. Too little money is available to support that research. As such, we simply don’t know as much as we ought to. But that’s no reason to oppose pronatalism! We only learn “what works” by doing stuff! Be the natural experiment you wish to have studied in the world! You have got to be manifesting quasi-experimentality!

All that to say, yes, for the last time, pronatal policy works. In fact, prominent state-sponsored politico-religious leaders bullying people into having kids by suppressing the relative social status of low-fertility people is very effective! Weirdly enough though, “status transfer interventions” are by definition coercive (status is always nonconsensual) but often supported by people who oppose pronatalism!

Think about it: if a religious leader says, “Babies are so wonderful and good we love babies we admire people who have babies we must admire motherhood and parenthood and babies babies babies babies babies!” or whatever, and that raises fertility, how did it do that? The simplest answer is, “Coreligionists perceived that the social status gain from having babies rose and so decided the cost was worth it.” But social status is always zero-sum! Of necessity if you raise one person’s social status you are relatively lowering not-that-person’s status, and those people likely did not consent. Thus, weirdly, “we just need more pro-family vibes and rhetoric and motherhood valuation etc etc” ends up being one of the more obviously freedom-inconsistent methods of pronatalism available. “Quietly transferring some diffuse public resources to parents in a way where nobody feels specifically targeted” is much more “freedom-consistent,” but also not as “familistic.” It’s just about the hard math on babies. But it’s literally less likely to make people feel that their freedom is constrained.

Say It With Me: Pronatalism

Above I said that public-rhetoric efforts may actually be kind of freedom-inconsistent, and above that I said I believe in freedom-consistent methods in terms of government policy.

But that’s in terms of government policy. No such constraint exists on private people. You can just bind your own freedom! You can just have opinions! You can say things are bad even if they shouldn’t be banned; you can say things are good even if they shouldn’t be mandated! “Pizza is delicious” does not imply the statement “We should force all people to consume pizza twice a week.”

How we talk does matter. It matters that we speak honestly and openly and not obscure our beliefs or facts in unhelpful language. It matters that, when we argue about words, there be some actual stakes in them.

And there are actual stakes in “pronatalism.” The stakes are twofold:

World-historic: as I said, this is an ancient battle we have been fighting against anti-humanism since forever. Speaking theologically, I note that there’s a certain curse after a certain garden which happens to mention fertility being costly. If you’re not living the reality that the pain and cost of family are literally the curse placed on mankind for our sin, and thus that good societies are those that strive to help people live rightly despite the curse, then c’mon what are you even doing here. The only reason “go forth and multiply” is even slightly tricky is because of the curse. God gave like the easiest command and he made fulfilling it super fun.

If we can’t stand up and say, “Yes, births are good, even from families that aren’t my family ideal, even from people very different from me, even from the poor or the dysfunctional or whoever,” if we cannot just say “Yes, it’s good to make more people,” then we are never gonna win, culturally speaking. Successful cultural norms are less than 5 words. Cultures run on rules of thumb, simplified scripts, efficient mental heuristics. Whatever our governmental views, the words we use to describe ourselves must be unambiguous. “Family” is, alas, very ambiguous. That’s why politicians love it. Everybody’s a family! It means whatever you want! Nobody is excluded! “births” or “babies” is concrete. It identifies and it excludes. It is therefore a credible candidate for a working social norm. “More babies.” Pronatalism.

I agree with Ivana Greco that a lot of people who brand themselves pronatalists are cringe. Also many are liars: they don’t support actual policies to yield more births, they just want to hassle women online. So it is in every tent: some people under it are charlatans. But we shouldn’t say “I’m for births, unless you ask me in Latin” just because some Latin-word-enjoyers are weirdos.

You’re not walking your own walk, or talking your own talk.

Like, you say messaging should be simple— but then do everything in your power to elide that ‘natalism,’ as a term, has been co-opted by political extremists, who do very much mean it in terms of cultural supremacy— racial, religious, or even nakedly partisan.

You write a bunch on how you should just be honest, but you’re not being honest by trying to group these cultural supremacists in one caveat paragraph of ‘communitarian’ natalism. These culture warriors are not just grandmas who want more grandchildren, pastors who want more kids in sunday school, etc.

By trying to ignore the current political moment, and the current political context of the use of the word ‘natalism,’ you are the one being dishonest.

There is a real and extent natalist political movement within movement conservatism in US politics, and among ultra-nationalist political movements world-wide, especially in Europe. That political movement frames natalism in terms of cultural supremacy, and often explicitly in terms of gender roles and proscribed family structures (stay at home moms, single earner families). However you want to frame it, that extant and growing political movement has in English language adopted the term ‘natalism’ to brand their movement, without any of your caveats.

If we can’t be honest that this movement is real and growing, then voters aren’t going to trust us either. There has to be a means of disavowing these people— they are not simply fringe figures, they include the Vice President of the United States of America. They are hosted and platformed at major political conventions. They have influential and sophisticated digital media ecosystems. Voters are familiar with them.

No matter how much lipstick you put on that pig, voters can still smell it and recognize it. So yeah, there does need to be language to distinguish ‘freedom natalists’ from this virulent and hateful political movement. And step one of that is recognizing the political platform these people have built, and establishing that you oppose their supremacist views, reject their gender essentialism, etc. And not just doing that in a throw-away mealy-mouthed caveat paragraph.

You are not grappling with current reality, you’re trying to find a way to avoid the conflict such a confrontation would entail.

I am...getting there. The term has always grated on me because it literally means pro-birth. Not pro baby or pro child or pro preschooler even when he's annoying you in public...

Obviously I want more births (I'd like to stay employed and I think babies are cute). But it feels like some of the most pronatalist conservatives are pretty apathetic toward giving those babies access to healthy food, good healthcare, schools.

Are you aware of any policies around free healthcare during pregnancy and childbirth (in a place that didn't already have nationalized healthcare) and did it change the birth rate?