What Do Lesbians Want?

The curious case of fertility statistics for same-sex partnered female households

This post will be very short. It’s a simple data exercise in which I demonstrate that the rise of nontraditional sexual identities is probably leading to measurement errors in some demographic methods, and as such the contribution of nontraditional sexual identities to demographic decline and to ongoing gender polarization may be understated.

Demographers tend to measure fertility “per woman” because female-specific factors such as gestational timing and ability to carry children to term are the broadest-defined rate-limiters for human reproduction. We don’t use “per woman” statistics out of some ideological preference for a femocentric statistical norm, but simply because at the broadest level of extraction, pubescence, menopause, age, and sex are the traits that regulate an individual’s ability to contribute to fertility, and pubescence and menopause are strongly related to age, so we usually consolidate down to age and sex.

This usually works well. But increasingly, this approach has a big problem. In Ye Olden Times, such as the ancient days of 1997 or 1321, both of which are Beyond The Wall of the great Awokening which shattered the timeline of history such that a person advocating normal positions from, say, 2005 is practically a political pariah in 2025, women mostly were partnered with men. There were singles yes, and a handful of two-female households, but this was rare. Today, it is common. How common? Here:

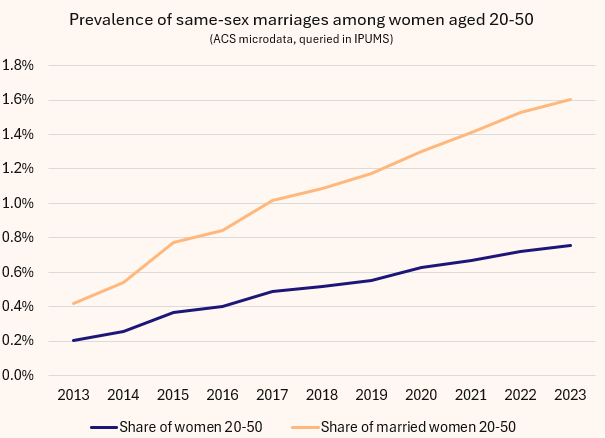

Just since 2013, females married to other females have risen from 0.2% of the female population aged 20-50, to almost 0.8%. Among marrieds, they have risen from 0.4% to 1.6%.

Small shares, but a rapid rise.

As such, it matters to understand these women for understanding fertility.

This matters because two-female households wreck some basic measurement strategies. For example, we usually like to ask women “How many children would you like to have?” and we infer that “to have” here means “to conceive, carry to term, bear in a live birth, and raise to maturity.” But if two lesbian women both say they would like to “have” 2 children, are they reporting a family-wide desired family size of 4 children, or 2?

To estimate society-wide desired fertility, we implicitly assume that we can measure just women and this will in turn tell us society-wide desires because men must pair with women to have children. The “men must” part remains true even for surrogacy or IVF, but the measurement part is tricky. We need to know how lesbian women interpret these questions!

So let’s investigate!

General vs. Personal Ideals

A quick and dirty way to untangle this is to leverage different questions about fertility preferences. I have a big survey that asks many such questions. For example, respondents are asked “How many children would you say is ideal for a family to have?” I did not invent this question, it comes from the General Social Survey. Crucially, it tells us how many children is ideal for a family to have: not the respondent individually, and this is definitely not something you should sum together for two lesbian partners!

We also ask a question about the number of children which would make a woman happiest, personally, to have. This question is a bit complex because it offers them a lot of flexibility in the answer beyond just “choose a number,” so I won’t bore you with it, but suffice to say it’s definitely a personal preference question.

How do these questions compare?

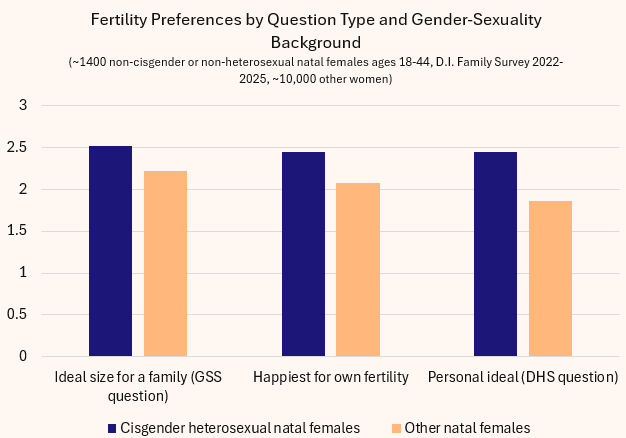

You can see that cisgender heterosexual natal females say the ideal family size is 2.5, while other natal females say it’s 2.2. Okay, fair enough, no surprise nontraditional gender/sexual identities are linked to slightly smaller ideal family sizes.

But now look at the happiest fertility, or the personal ideal where I replicated the question structure from the DHS surveys: cisgender heterosexual women report similar personal vs. general ideals, but other women have much larger gaps between general and personal ideals.

However, notice that the “other” group doesn’t have personal/happiest values that are half of cisgender heterosexual net females.

Here’s how this plays out.

If we tried to estimate “society-wide desired fertility” by summing every woman’s happiest parity and dividing by the number of women, we would be summing the desired fertilities of both women in any possible lesbian couple, and this would produce an estimate of desired fertility vastly exceeding their general ideals for “a family.” This is implausible.

It’s more plausible to think that when lesbian women report “personal” desires, they don’t literally mean desires for their own biological fecundity, but rather for their own social family. They want their family to have that number of children.

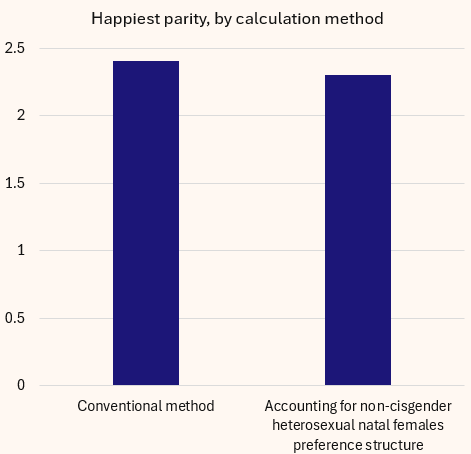

So let’s take two different approaches. Let’s calculate societywide desired fertility, first the conventional way (All women’s reports / Number of women), and next a modified way ( (Cisgender heterosexual women’s reports + ( Other women’s reports / 2) ) / Number of women ).

The effect is not enormous, but it’s also not nothing.

It really is the case that because non-heteronormative individuals may be in 2-female partnerships that we may be overestimating societal desired family size, because our conventional desired family size estimates assume heterosexual families.

After the paywall, I’ll explain what this means and why it matters.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Lyman Stone to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.