Why Twin Studies Are Garbage

They just aren't measuring what you think they are

Genes are important for lots of traits economists and sociologists and demographers like me like to study. And yet, actual genetic data is only rarely available in the datasets we use, and so we usually can’t easily control for genetic confounding. One way researchers have historically tried to get around this is through various kinds of kinship studies— we know monozygotic twins are genetically virtually identical, dizygotic twins extremely similar, full siblings more similar than half-siblings, etc. Assuming correct reporting of parentage, with data on traits of kin we can in theory get an idea of just how “heritable” certain traits are i.e. how predictable they are from the genetic-similarity-weighted traits of others in your kin-group. Models that do this vary in complexity and which kinds of kin-ties they leverage, but the central focus of these models has always been on twins. If identical twins turn out to be identical on a certain trait (say, eye color), then that trait is probably extremely genetic. If identical twins turn out to be variable on a certain trait (say, religious belief) then that trait is probably not extremely genetic.

Twin studies almost uniformly find nonzero heritability. It’s vanishingly rare to run a twin study and come away finding that there’s no genetic component to a trait of interest. This is the fundamental stylized fact underlying “hereditarianism,” i.e. the modern revival of the idea that most differences in traits across groups which matter for society are basically just genes. Whatever the other arguments, the central thing hereditarians almost always fall back on is that twin studies virtually always turn up nonzero heritabilities and that twin studies are so intuitive and so obviously genetic that they can’t be refuted.

Today I shall refute 100% of twin studies ever published and explain why they should probably no longer be published.

Peanuts

To explain the principle of why twin studies are bogus, it’s best to use a clear example that everybody intuitively “gets,” a trait we’re all familiar with where the various scientific elements of the argument are not in major contention. For that, we will focus on peanut allergies. Note that this section is substantially a reproduction of stuff I published in a prior post, but there’s new content later in the post.

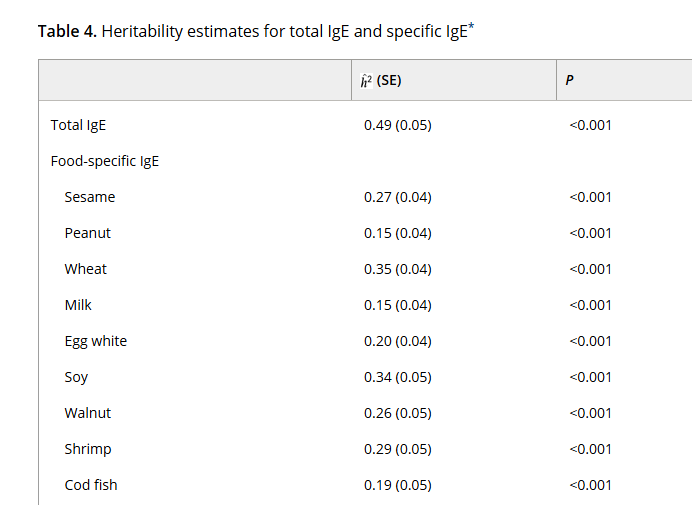

Food allergies run in families. So it’s logical to suspect they’re genetic. Here’s some estimates of heritabilities of various food allergies taken from twin and other kinship studies:

Now, that’s from a big family study. What if we focus more narrowly on twin studies where gene-sharing is more concretely quantifiable?

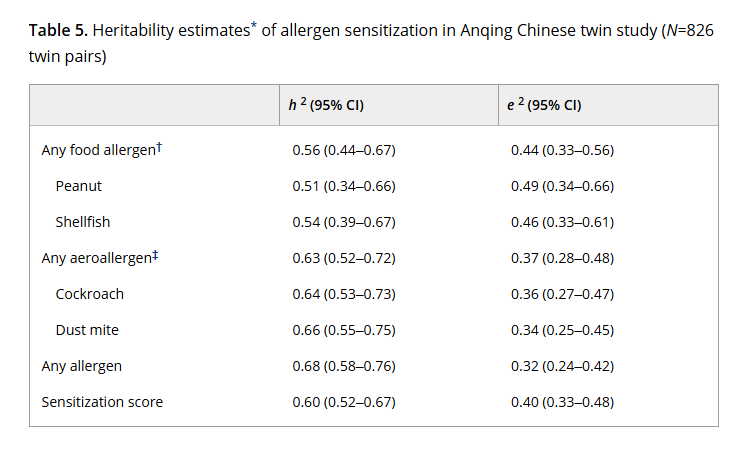

One twin study of peanut allergies suggest 85% genetic heritability. Another suggests 51%:

Another study doesn’t provide a heritability estimate, but it does tell us that MZ twins have much higher concordance rates for peanut allergies than DZ twins.

As you might expect, GWAS studies have identified specific genes related to peanut allergies. The two genes most strongly implicated for peanut allergies in that study have become progressively more common over the last 10,000 years in European-ancestry populations. For the first gene, rs9275596, the peanut-allergy allele is T, and it has gotten much more common over time, rising from basically 0% of hunter-gatherer populations in Europe to about 1-in-3 of modern Europeans.

The next major identified gene, rs7192, has a peanut-allergy allele of T; the graph below shows the frequency of G rather than T, so the decline in G-frequency is implicitly a rise in T frequency. You can see for hunter-gatherers, about 60% had G (non-allergic gene), whereas today Europeans have about 1-in-3 G; so the allergy-predicting gene rose from 40% to about 66%.

By the way, these genes also predict celiac disease!

So peanut allergies are genetic, right?

Well… no, they’re not. See, peanut allergies are almost entirely environmental. That study above that showed concordance rates but not heritabilities also found that all food allergies were mediated by atopic dermatitis. Kids who had a specific skin condition also had more food allergies even if their twin didn’t. That’s interesting since, while atopic dermatitis does have a genetic component, it has a huge environmental component too, fluctuating with season and living conditions. Anybody with atopic dermatitis can tell you the conditions that cause flareups for them, meaning there’s obviously a massive environmental component at work. If peanut allergies are so correlated with atopic dermatitis, that points to major environmental factors.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Lyman Stone to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.